Passion and Violence

Passion and Violence

Why was this film made?

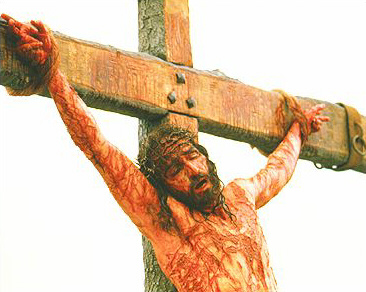

The Passion of the Christ is a very well-made film. With all the potential to be over the top or overbearing, it is acted with restraint and shot without cliche. The violence is brutal, but rarely gratuitous. And while the imagery, cinematography, and music owe a bit too much to The Lord of the Rings - as does the rendering of Aramaic as something quite similar to elvish - it is, after all, a Hollywood film. As with other Hollywood epics, you either buy into the conventions or you don't. And as with other great ones, if you do buy in, it's an emotional, visceral ride.

In part because of these cinematic virtues, and in large part because of how the narrative was shaped, The Passion of the Christ filled me with rage. Let's put it this way: at the end of the film, I wanted to kill Jews. Either that, or move to Israel and work on its nuclear program.

To debate whether or not this film is antisemitic, as many Jewish critics are doing, seems to me beside the point. The question is why, why in God's name specifically, anyone would want to distort the Biblical story of the Passion so as to emphasize its brutality, the villainy of its antagonists, and the overall horror of the sacrifice of the Christ?

This is not a rhetorical question, and I mean to answer it, seriously and religiously. First, though, it is important to understand that the answer is not "this is what the Bible says." Having spent two years studying the gospels in graduate school, and now having at last seen the film, I can confirm that it is indeed a vast distortion of the gospels. There are three primary changes: the violence, the Jews, and the magic.

First, Gibson has added large swaths of extra violence to the Biblical narrative. The film's long scourging of Jesus - in which we watch his skin being torn off by flaying (the Talmud relates the grisly scourging of Rabbi Akiva, which I remember being terrified by as a child) - is not mentioned, though it did happen before some crucifixions. The gospels do not relate that the Romans turned Jesus face-down on the cross before it was raised, or that he was thrown off a wall prior to his interrogation by the Sanhedrin. Nor, it may surprise you to learn, is there any mention of Jesus being nailed to the cross in the gospels themselves - this tradition came afterwards. But the film includes all of this and more, with a Hollywood emphasis on gore. Whereas the gospels spend hardly any time on the violence of the Passion (and a great deal of time on Christ's submission to it), we are shocked throughout the film by whips tearing into skin, nails being driven into hands and feet, scourges tearing off hunks of flesh, beatings, chainings, sadism, ravens poking out eyes, and throughout it all the merciless stare of Caiaphas the high priest, who is responsible for this innocent man being brutalized.

First, Gibson has added large swaths of extra violence to the Biblical narrative. The film's long scourging of Jesus - in which we watch his skin being torn off by flaying (the Talmud relates the grisly scourging of Rabbi Akiva, which I remember being terrified by as a child) - is not mentioned, though it did happen before some crucifixions. The gospels do not relate that the Romans turned Jesus face-down on the cross before it was raised, or that he was thrown off a wall prior to his interrogation by the Sanhedrin. Nor, it may surprise you to learn, is there any mention of Jesus being nailed to the cross in the gospels themselves - this tradition came afterwards. But the film includes all of this and more, with a Hollywood emphasis on gore. Whereas the gospels spend hardly any time on the violence of the Passion (and a great deal of time on Christ's submission to it), we are shocked throughout the film by whips tearing into skin, nails being driven into hands and feet, scourges tearing off hunks of flesh, beatings, chainings, sadism, ravens poking out eyes, and throughout it all the merciless stare of Caiaphas the high priest, who is responsible for this innocent man being brutalized.

Second, The Passion of the Christ makes it unambiguous who is responsible for the death of Christ: the Jewish leadership. Although the gospels repeat, over and over, that Jesus is giving himself up to fulfill a prophecy and his mission of salvation, the film spends at least equal time blaming the agents of that mission: i.e., the Jews. Pilate, a notorious murderer according to contemporary sources, is depicted as the tragic conscience of the film, coerced into spilling innocent blood by Caiaphas and his fear of a Jewish rebellion. (Gibson also chose to include John's account, absent in the other gospels, of Pilate engaging in a philosophical conversation with Christ himself.) Nowhere in the gospels is Caiaphas or any other Jew mentioned as being present during Jesus' torture, and nowhere is Caiaphas - who was installed and paid by Rome - regarded as anything like the man with power over the entire situation, as he is throughout The Passion. Indeed, when Pilate wanted to quell a rebellion, he knew perfectly well how to do so: by killing and/or crucifying hundreds of Jews at a time. Nowhere do the gospels relate the Jewish leaders making up additional scurrilous and false charges against Jesus, e.g., that he was telling Judeans not to pay their tribute to Rome, when the substantive charge of blasphemy failed to stick. In short, whatever anti-Judaism is in the gospels, and there is plenty, Gibson vastly augmented it in his film. What's more, the priests and Pharisees all look like Jews - you know, the beard, the nose, the sidelong glances, the funny clothing - whereas the everyday Jews, Jesus himself, and most of his disciples look like Protestants.

Finally, The Passion of the Christ chooses to emphasize and invent supernatural aspects to the passion story that are not in the gospels. At the moment of Christ's death, a large earthquake shakes Jerusalem, causing chambers in the Temple to be destroyed. Judas is driven by demons, whom we see, to kill himself (the gospels just relate that he hanged himself, presumably out of guilt). Jesus miraculously heals the ear of a soldier whom one of his disciples attacks, an anecdote present only in the gospel of Luke, but included in the film. And throughout, Satan -- not present in the gospels' accounts of the passion -- lurks at every turn, a pale, androgynous figure whom only Jesus is able to see. The gospels' overriding message seems to be one of acceptance of Divine destiny. Jesus refuses to defend himself, telling us his death must take place in this way in order to fulfill his Divine mission. In the film, the overriding message is the supernatural Christ and the blindness of those who don't get it. This is the mythic, Catholic Jesus, not the rabbi, Protestant Jesus: Jesus the son of God, who died on the cross for our sins, not Jesus the teacher of wisdom. Jesus dies as an act of love, and he loves his enemies even on the cross, but it is the cosmic significance of the passion that is emphasized. Yes, Jesus is shown convincing some disciples through his words, but most of them he gets just with a look; Roman guards, Simon carrying the cross, Mary Magdalene - all are converted just by gazing into Jesus's eyes. They see. The Jews are blind.

Passion and Violence

Jay Michaelson

A Song of Ascents:

The News from San Francisco

Sarah Lefton

Bush the Exception

Samuel Hayim Brody

The Wrong Half

Margaret Mackenzie Schwartz

God Had a Controlling Interest

Hal Sirowitz

Schneiderman

Eliezer Sobel

Josh hosts a party

Josh Ring

Archive

Our 450 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Winter 2003-2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

News & Events

Contact Us

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

The Truth about the Rosenbergs

Joel Stanley

The Art of Enlightenment

Jay Michaelson

With a Bible and a Gun

Samuel Hayim Brody