Why these three distortions -- adding violence, vilifying the Jewish villains,

and emphasizing the supernatural? In part, it is because The Passion of the Christ is an extremely Catholic film - it is puzzling that so many Protestants are rushing to see it, since the Jesus portrayed in the film is the supernatural Christ, not the ethical one; the one of saints, hell, and apocalypse, not of common sense readers of the Bible. This is the Christ who says "No one can reach the father except through me," not "Turn the other cheek"; we hear the full Last Supper/communion speech ("this is my body...") but nothing like "it is easier for a camel to pass through the head of a pin than for a rich man to enter heaven."

Why these three distortions -- adding violence, vilifying the Jewish villains,

and emphasizing the supernatural? In part, it is because The Passion of the Christ is an extremely Catholic film - it is puzzling that so many Protestants are rushing to see it, since the Jesus portrayed in the film is the supernatural Christ, not the ethical one; the one of saints, hell, and apocalypse, not of common sense readers of the Bible. This is the Christ who says "No one can reach the father except through me," not "Turn the other cheek"; we hear the full Last Supper/communion speech ("this is my body...") but nothing like "it is easier for a camel to pass through the head of a pin than for a rich man to enter heaven."

But the particular emphasis on the violence and the perfidy of the Jews, the addition of detail - this film is too odd to simply say "it is as it was," since it isn't how the gospels say it was. Nor, unlike some of my colleagues, do I believe the answer lies in either antisemitism or cynicism. Gibson is too religious for that. So, I return to my question, with a new emphasis: why was this film made?

Let's let Gibson answer first. He said on NBC's "Today Show" that the point of the film's violence was to show "the enormity of the sacrifice":

| I want the full savagery of it to sort of like, you know, jump out of the screen at you. And at the same time, this is the trick, it's to be moved by it, not just repelled by it. |

We are meant to be moved because Christ willingly gave up his life to bring salvation to others. Each crack of the whip, coupled with Christ's acceptance and equanimity, is more inspiration. In fact, the movie often had this effect on me - Jim Caviezel has the mystic's eye down pat, and as a religious person myself, I was inspired. It would be a mistake to think that the film is "about" the violence, or the Jews; to think so is to manifest precisely the blindness that the gospels, film, and centuries of Christian tradition ascribe the priests and Pharisees. No - it's about God.

In this Light, we must understand that - Passion plays and their ascriptions of blame notwithstanding - this was Christ's own decision, God's own decision. It had to be this way. As Jesus says himself when he is arrested,

|

All those who draw the sword will die by the sword. Do you think I cannot call on my Father, and he will at once put at my disposal more than twelve legions of angels? But how then would the Scriptures be fulfilled that say it must happen in this way?

(Matthew 26: 53-54) |

Tellingly, this rebuke is issued to the disciple who cuts off the ear of the soldier. The gospels themselves are well aware of the effects of violence, and, there, Jesus's nonviolence seems emphasized in contrast. Yet Gibson leaves out the last two lines, includes a shot of the bloodied ear, extends the fight scene, and then focuses on the miraculous healing. The Passion of the Christ revels in violence, and it is shown to audiences who are not Jesus Christ, and who, like me, are likely to be enraged by the suffering of the innocent. Of course, we should try to imitate Christ and understand that God is the sole true power. But why tempt us so? Why omit the anti-violence cues which the gospels themselves provide, while playing up the violent ones? What is to be gained by this graphic display of violence and blindness?

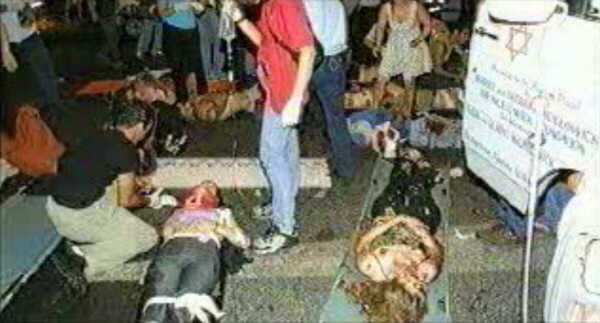

A month before The Passion of the Christ was released, the Israeli government

decided to place on its foreign affairs website graphic videos of the aftermath of

suicide bombings. The videos, available at www.mfa.gov.il are intensely disturbing, and we have captured only the milder images here. The purpose of the move was twofold. Specifically, it was designed as a PR campaign launched in connection with the Palestinian effort to convince the International Court of Justice in the Hague to declare the Israeli "security fence" a violation of International law - an effort that most legal observers believe will easily succeed, particularly since Israel has refused to participate in the tribunal. (Israel claims this is because it does not want to recognize

the court's authority, but it's more likely that they

knew they would lose.) More generally, the videos are meant

to counter a years-long campaign by the Arab world of airing shocking, graphic imagery of maimed human corpses and mutilated bodies in connection with - choose your political flavor - reporting on the Intifada or stoking the flames of hatred against Israel.

Passion and Violence

Jay Michaelson

A Song of Ascents:

The News from San Francisco

Sarah Lefton

Bush the Exception

Samuel Hayim Brody

The Wrong Half

Margaret Mackenzie Schwartz

God Had a Controlling Interest

Hal Sirowitz

Schneiderman

Eliezer Sobel

Josh hosts a party

Josh Ring

Archive

Our 450 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Winter 2003-2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

News & Events

Contact Us

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Radical Evil

Michael Shurkin

Thinking Despite Doubt, Feeling Despite Truth

Jay Michaelson

Antifada Paratrooper

Michael Kuratin