With a Bible and a Gun:

With a Bible and a Gun:The Prophetic Justice of Johnny Cash

"I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die." Lazy critics sometimes write this line as if it were a visceral ode to violence, a vicarious thrill. I myself once interpreted the lyric this way in an argument with a conservative friend as a way of defending lurid images in hip-hop: "Look, singers as far back as Johnny Cash have been talking about this kind of stuff - I don't hear you complaining about country music." But it does Cash a disservice to attribute this sort of aggressive sentiment to his work without looking any deeper; Cash, who died last month, was anything but a proud, thuggish outlaw. So, in memory of the Man in Black, let's look deeper.

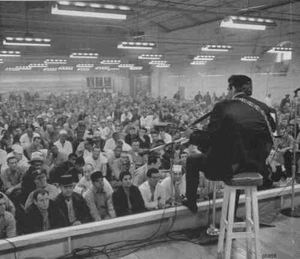

On the 1968 live recording of "Folsom Prison Blues," Cash sings the infamous line

to boisterous cheers from his captive audience. We can't know exactly what these

cheers mean, although Stephanie Zacharek of Salon has offered an intriguing

possibility: that they are cheering Cash's step down not merely to their level but to

below their level (or possibly, 'above' their level in toughness). Most

of the prisoners for whom Cash was performing probably had not committed any

such cold-blooded crime. I am reminded of Woody Guthrie's cri de coeur

against any "song that makes you think that you are not any good . . . a song

that makes you think you are just born to lose" and wonder if Woody (who died in 1967)

loved Johnny Cash.

The cheers almost cover the next line: "When I hear that lonesome whistle blowin' /

I hang my head and cry." Cash's character in "Folsom Prison Blues"

isn't unrepentant; he wonders what it was in him that was capable of murder.

Like Merle Haggard's wayward son in "Mama Tried," Cash's killer laments his

failure to heed the wisdom of his mother. And like Clint Eastwood's old

villain-hero in Unforgiven, he knows the power of human evil - because he has wielded it himself. In the end, "I shot a man in Reno" isn't a crow - it's a wail.

The cheers almost cover the next line: "When I hear that lonesome whistle blowin' /

I hang my head and cry." Cash's character in "Folsom Prison Blues"

isn't unrepentant; he wonders what it was in him that was capable of murder.

Like Merle Haggard's wayward son in "Mama Tried," Cash's killer laments his

failure to heed the wisdom of his mother. And like Clint Eastwood's old

villain-hero in Unforgiven, he knows the power of human evil - because he has wielded it himself. In the end, "I shot a man in Reno" isn't a crow - it's a wail.

Most of Johnny Cash's songs were wails. It's tough to think of another modern singer whose catalog has fewer upbeat entries. Even in his more popular numbers, like "Ring of Fire" and "I Walk the Line," rousing arrangements accompany lyrics that skirt the edge of darkness. "I Walk the Line," for example, ultimately is about affirmation of fidelity and the straight and narrow, yet it captures a moment in an outlaw's life when he reins himself in for his girl. If it were a story-song instead of a moment-song, one could easily imagine the outlaw losing the girl, losing control. "Ring of Fire" is a love song that evokes the fires of hell ("I fell into a burning ring of fire / I fell down, down, down and the flames went higher"). The only Cash hit that really stands out as light-hearted or funny is the Shel Silverstein-penned "A Boy Named Sue," about a boy whose father names him "Sue" so he'll grow up tough. But even "A Boy Named Sue" is only funny in a rough-and-tumble, laugh-through-the-tears kind of way. Sue finds his father in a bar and attacks him; they tear at each other through "the mud and the blood and the beer" until the father delivers his exculpatory address: "Ya ought to thank me, before I die / For the gravel in yer guts and the spit in yer eye / 'Cause I'm the son-of-a-bitch that named you 'Sue'."

What all these songs have in common is the sense of ever-present danger, of life as a dangerous thing that wants to hurt you and will take whatever it can from you whenever it gets the chance. The story of Johnny Cash is the story of describing that hurt.

Carrying Light into Dark Times

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

With a Bible and a Gun:

The Prohetic Justice of Johnny Cash

Samuel Hayim Brody

Season of Revision

Jay Michaelson

Primal Scream Judaism

Temima Fruchter

More than This

Dan Friedman

Josh's Dinner

Josh Ring

Archive

Our 390 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Buy online here

About Zeek

Events

Contact Us

Links