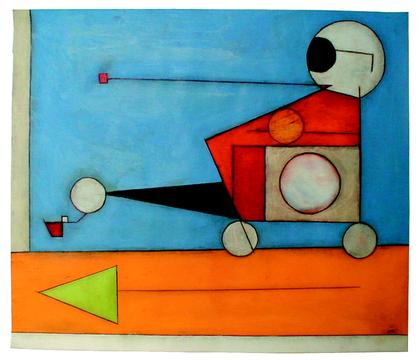

The Wheel World

The Wheel World

Reviewed:

Rory O'Shea was Here (Damien O'Donnell, 2004)

Pumpkin (Anthony Adams, 2002)

Palindromes (Todd Solondz, 2004)

Saved! (Brian Dannelly, 2004)

Murderball (Henry Alex Rubin, 2005)

When the worth of Cinema is being weighed on the Day of Judgment, what might save it from the fiery inferno is its ability to tell the personal story. At its best Cinema shows us the spark of divinity in those fellow human beings at whom otherwise we might not have looked. For better or for worse, this power seems far greater than Cinema's ability to engage with "abstract" issues, in favour of the human costs the issues exact. We may not be persuaded of the historical necessity of outlawing the death penalty, for example, but after watching Dead Man Walking or Dancer in the Dark, we are given significant pause to think.

This summer sees the US release of the latest two films to tell the personal stories of people in wheelchairs. Rory O’Shea was Here (previously Inside I’m Dancing) has finally been released on DVD, and Murderball, a documentary about quadriplegic rugby in the Paralympics will be hitting (and I use the word "hitting" advisedly) North American cinemas this summer. Like the death row stories above, these films likewise give us pause to think not only about the way that societies think of disability but about how that process of thought reflects on the societies themselves.

I. Does He Take Sugar?

Growing up in England I occasionally heard a radio program called "Does He Take Sugar?" It was a news magazine program of general interest but designed to carry stories especially pertinent for the disabled community. The title comes from the way people in wheelchairs are often cut out of conversation: it is asked by a person offering a welcoming cup of tea not to the wheelchair-bound guest, but to the able-bodied person pushing him. However well-meaning, such acts imply that once someone is in a wheelchair neither are they capable nor worthy of conversation.

Ten years on, I can remember none of the particular news stories, but the title of the program has stuck with me. The title was always deliberately ironic, since the program (on national radio) was all about the disabled community actually having the wherewithal to voice its own concerns and stories. It was, however, a stroke of genius to put the implicit focus of the program (and the listener) on the question of who exactly is deemed to be part of everyday conversation and why those judgments are made.

As the radio program’s title suggests, one of the central problems of being in a wheelchair is the image of the wheelchair in the minds of those walking around it. This problem is reflected not only in how these walkers ignore the person in it, but also in the type of language used to describe the conditions of those in them. Euphemisms abound. In the film Pumpkin, the climactic sporting event is called the Challenged Games and the characters are always searching for acceptable words to describe a group they would rather consider unacceptable. In Saved! -- the 2004 comedy about the problems of growing up at a parodically Jesus-loving high school -- Hilary Faye (Mandy Moore) asks her wheelchair-bound brother Roland (Macaulay Culkin) "why do you have to make people feel so awkward about your differently abledness."

The struggle to have a voice that is heard, understood, and listened to, is the crucial struggle in both Rory O’Shea was Here and Pumpkin (2002) as their protagonists struggle against the handicap of being thought "handicapped." In each of these films a major character is in the situation of being in a wheelchair and also, due to cerebral palsy or a similar ailment, largely incomprehensible to his carers. Pumpkin Romanoff (Hank Harris) practices and practices, in order to make his beloved Carolyn (Christina Ricci) understand and engage with him . Eventually his diction becomes clearer, his verbal transformation as central to his being taken seriously as his increasingly confident walking.

In Rory O’Shea was Here there is no such magical improvement of condition. Michael (Steven Robertson) has the same speech problem as Pumpkin, but any gain in clarity is marginal. It takes the entrance of a listener, title character Rory (James McAvoy), to transform the sounds into meaning. Initially Rory’s ability to hear Michael’s meaning through his sounds seems miraculous to Michael, but for Rory it is not Divine but rather the fairly banal product of having been schooled next to several people who spoke like Michael. Once one person listens to him, Michael becomes someone worth hearing and, by the end of the film, Michael has earned the respect that should have been his initially. Not only Rory has listened to him, but so have enough people to get him into law school.

Golden Calf

Jacob J. Staub

Israel on Campus

A Conversation with Sam Brody and Zach Gelman

Samaria for Rent

Margaret Strother-Shalev

Does Mysticism Prove the Existence of God?

Jay Michaelson

Patrolling the Boundaries

of Truth

Joel Stanley

The Wheel World

Dan Friedman

Archive

Our 700 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Summer 2005 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

Limited Time Offer

Subscribe now and get

two years of Zeek for

25% off regular price.

Click this button

to purchase:

From previous issues:

My First Shabbos

Josh Gets his Checkup

Surrender

Jennifer Waters

Josh Ring

Niles Goldstein