Dan Friedman

III. Disabled is the new black

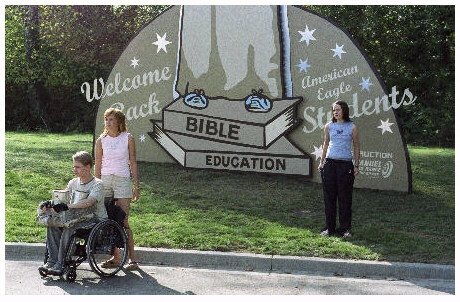

We hate to deal with difficulty. Although we know that the world is a diverse place, and better for it, we try to flatten it out – it’s just easier that way. We try to put people and things into readymade pigeonholes that then become accepted norms rather than the contingent categories that they really are. In both Pumpkin and Saved!, groups of young, wealthy, and extremely sheltered women come into contact with both the diversity and adversity that explodes the self-satisfied smugness of their worldviews. For these American films, race and religion are intertwined practically. In Saved! the Jew, the unwed mother, and Roland in his wheelchair are the exemplars of difference.

We hate to deal with difficulty. Although we know that the world is a diverse place, and better for it, we try to flatten it out – it’s just easier that way. We try to put people and things into readymade pigeonholes that then become accepted norms rather than the contingent categories that they really are. In both Pumpkin and Saved!, groups of young, wealthy, and extremely sheltered women come into contact with both the diversity and adversity that explodes the self-satisfied smugness of their worldviews. For these American films, race and religion are intertwined practically. In Saved! the Jew, the unwed mother, and Roland in his wheelchair are the exemplars of difference.

In Pumpkin the physically disabled (including people in wheelchairs) appear as just another diverse group, albeit one to be pitied and reviled, to whose inclusion lip-service must be paid. Yet there is a crucial difference: unlike race, or religion, the condition against which the bigot is prejudiced is all too easily emulated. This is the case for Carolyn’s tennis star boyfriend Kent (Sam Ball) whose car crash leaves him in a wheelchair. This tragic turn of events is part of a disturbing double play in the closing scenes, where Kent plays noble victim from the wheelchair while Pumpkin proves heroic transcendence by winning a footrace (thus winning the Challenged Games, but betraying all those who are heroic but irrevocably wheelchair-bound).

Notwithstanding this disturbing interchangeability of cripple and jock hero, Pumpkin’s situation is continuously compared in the film to that of pre-Civil Rights blacks. For example, Carolyn says that Pumpkin’s "not going to sit at the back of the bus" which counterbalances the exquisite bigotry of her mother when she warns Carolyn against boys from "other … communities." The way in which discrimination is measured is in racial terms.

The intersection of race and disability is depicted in characteristically perverse ways in Todd Solondz's latest film, Palindromes. There, the question of diversity is barely interrogable because the horror of the thought of difference is too appalling for meaningful justification. We are asked, without any explanation, to accept two African-American actresses (one morbidly obese) portraying Aviva, the teenage daughter of upper-middle class Jewish Joyce Victor (Ellen Barkin); it is as if we are being dared to say that race (and body size) doesn't matter, when it clearly, to the audience, does. Here, too, disability is used as a form of difference, again juxtaposed with race. Joyce explodes at the thought of having to explain why teenage pregnancy is not a viable choice for her daughter, whereas the "Sunshines," Jesus-loving radicals who conspire to kill abortionists, adopt children with a spectrum of "differences." The actor portraying Aviva in the sequence with the Sunshines is Sharon Wilkins, the morbidly obese African-American, yet the dissonance seems less acute in the presence of all the other "different" people. The fragile consensus cannot hold: the presence of difference is the cause of that realization not of the problem.

The inclusion of wheelchairs provides a subject using which filmmakers can treat diversity intelligently and viscerally without having to give a history lesson. Yet the glib comments made by the ‘popular girls’ of each film about inclusion of religion and colour into the extremely narrow and self-centred worlds of Pumpkin and Saved! do little more than remind the viewer how tokenistic racial and ethnic diversity can be when there is no understanding of the Other. In the complexities of Palendromes, the documentary realism of Murderball and in Michael's ability in Rory O’Shea was Here to give an account of himself, the easy equivalencies of "difference" are effaced. Perhaps the contingent categories of race are too strong to allow disability become a category itself, or perhaps even "disability" is itself too marginalizing and generalizing a category. It is only when each personal story is taken on its merits – that race is not the only language for difference – that we begin to see the real wheel world.

Ashes and Snow and the Nomadic Museum

June, 2005

A masculinist encounters The Grrl Genius Guide to Sex (with other people)

June, 2005

Walking through The Gates

March, 2005

On the anthropology of contemplative practice

February, 2005

November, 2004

The spirit and the machine

August, 2004

Faux feminism on the silver screen

June, 2004

Two Zeek editors discuss running, spirituality, and Running the Spiritual Path

December, 2003

May Tricks: Reel-or-Dead?

June, 2003

August, 2002

The personal politics of this summer's blockbusters.

June, 2002

A review of "The Paradise Institute," a meditation on frames, judgment,

and power.

May, 2002

CBS's packaging of the '9/11' documentary reveals exactly what America

fails to understand about September 11.

April, 2002

Golden Calf

Jacob J. Staub

Israel on Campus

A Conversation with Sam Brody and Zach Gelman

Samaria for Rent

Margaret Strother-Shalev

Does Mysticism Prove the Existence of God?

Jay Michaelson

Patrolling the Boundaries

of Truth

Joel Stanley

The Wheel World

Dan Friedman

Archive

Our 700 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Summer 2005 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

Limited Time Offer

Subscribe now and get

two years of Zeek for

25% off regular price.

Click this button

to purchase:

From previous issues:

The Red-Green Alliance

Masoretic Orgasm

Five Groups to be Angry at after September

11

Dave Hyde

Hayyim Obadyah

Jay Michaelson

Email us your comments

Email us your comments