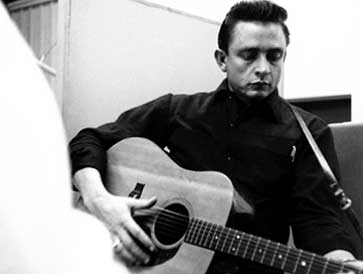

This brings us to that protest psalm that gave Cash his most famous moniker, "The Man in Black." The song powerfully conveys Cash's religious sense of social justice. It's well-known that Cash's custom of wearing black to rhinestone-studded country western events was a spitball in the eye of Nashville complacency. "The Man in Black" was the song in which he explained his choice:

|

I wear the black for the poor and beaten down Livin' in the hopeless, hungry side of town I wear it for the prisoner who's long paid for his crime But who's there 'cause he's a victim of the times.

|

And yet this is no call to revolution; no program for action is contained in Cash's lyrics. He's just waiting for "a move to make a few things right," and until then he takes the black on himself. "I'll try to carry off a little darkness on my back / 'Til things are better, I'm the man in black." Cash's most intensely other-focused song is also intensely personal, because what he's doing here is presenting himself as a most basic religious figure - the one who by his very presence acts as a reminder to society of its moral failure and materialism - the prophet, here delivering the words of Jesus: "About the road to happiness through love and charity / Why, you'd think he's talkin' straight to you and me." But Cash's particular theological dogma doesn't matter to the listener; one is struck with a profound feeling that this religiosity

is true; that this is what matters, that Cash is

getting it right and to hell with the rest of them.

His presence is an incarnated moral imperative.

That unique, baritone, demanding, serious, masculine voice is constantly calling to us, asking us the same question: if we can't muster up this kind of empathy and compassion ourselves, whatever we say we believe, then what are we good for? Condense all these messages into one moment and you understand the proper impact of the sight of Johnny Cash wearing his black.

And yet this is no call to revolution; no program for action is contained in Cash's lyrics. He's just waiting for "a move to make a few things right," and until then he takes the black on himself. "I'll try to carry off a little darkness on my back / 'Til things are better, I'm the man in black." Cash's most intensely other-focused song is also intensely personal, because what he's doing here is presenting himself as a most basic religious figure - the one who by his very presence acts as a reminder to society of its moral failure and materialism - the prophet, here delivering the words of Jesus: "About the road to happiness through love and charity / Why, you'd think he's talkin' straight to you and me." But Cash's particular theological dogma doesn't matter to the listener; one is struck with a profound feeling that this religiosity

is true; that this is what matters, that Cash is

getting it right and to hell with the rest of them.

His presence is an incarnated moral imperative.

That unique, baritone, demanding, serious, masculine voice is constantly calling to us, asking us the same question: if we can't muster up this kind of empathy and compassion ourselves, whatever we say we believe, then what are we good for? Condense all these messages into one moment and you understand the proper impact of the sight of Johnny Cash wearing his black.

Cash's career lapsed for many years; apparently concept albums about Native Americans weren't Nashville radio stations' number-one choice for airplay. But he made a much-heralded comeback in the 90's as he worked on the American series with legendary hip-hop and rock producer Rick Rubin. Die-hard country fans looked down on these albums, littered as they were with covers of hard-rock and folk songs, and generally lacking much new material. But what Cash was out to tell us here was that he knew what a good song was, and that you could understand even more about the man himself by hearing him play songs you'd heard others sing already. I don't know if Chris Cornell and Trent Reznor understood the honor they were done by Cash's appropriation; "Rusty Cage" and "Hurt" simply make more sense when rendered acoustically, sung by that voice with its religious understanding, its knowledge of right and wrong, its decades of experience and wisdom. And yet he also proved he still had it: "I'm Leavin' Now," off of American III: Solitary Man, and "The Man Comes Around," from Cash's last album American IV: The Man Comes Around, stand with some of the best of his earlier work.

Carrying Light into Dark Times

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

With a Bible and a Gun:

The Prohetic Justice of Johnny Cash

Samuel Hayim Brody

Season of Revision

Jay Michaelson

Primal Scream Judaism

Temima Fruchter

More than This

Dan Friedman

Josh's Dinner

Josh Ring

Archive

Our 390 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Buy online here

About Zeek

Events

Contact Us

Links