Doctor

Doctor

1962. A city bus on a wet afternoon.

The familiar aroma of used gasoline lulled these anxious riders into rest. The stops and starts rocked them – little bundles of privacy looking through dark windows at endlessly familiar dark, wet streets.

There was a sheen of shadow to that particular sociality, an etiquette for public transport, standing up to give elders a seat.

Anonymous shopping, schlepping. Wet tabloids in weary laps. Here and there, a tender mother/daughter conversation. Galoshes.

“Why does that man have no legs?”

“Shhh. Don’t point.”

Eva’s mother’s tired, wet burdens. Their bus was inching home now, home to President Kennedy, men in space.

“Mommy, something happened in school.”

“What was it? Tell me.”

For the rest of her life, Eva’s youth would loom before her, retrospectively. Every rainy day would recall these childhood rainy days with her over-worked mother on creaky, over-crowded green busses, crawling down their avenue.

“Can you take me there?” (Pointing at an ordinary object of international significance like the UN.)

Their conflicts.

A war, several consumer revolutions and some presidents later, as a seventeen year old freethinker, Eva got off the same humbling bus on a similarly rainy Saturday morning to get an IUD. It was the nineteen seventies, the last gasp of consciousness. High school girls were wild horses then, black beauties in pea coats, long straight hair and looming hips under painters’ pants. Someone right before them had abolished the dress code. Now those restraints were history, not just forgotten but unimaginable. Sex had become more than an option. It was an obligation and a responsibility. It was who you were. To be a virgin was to not be.

The rain fell into her pockets, flooding the street where the public health clinic sat in a Puerto Rican neighborhood called Chelsea. The girls at school openly told each other about this place, but all went there alone. No boyfriend accompaniment. No chum. It was widely understood to be a solitary endeavor rather than a secret. So, white Eva waited on line with Latin guys in frayed army jackets fearful of The Clap. Big afros, they cupped cigarettes in the hallways, acne red from the cold. Transistor radios played. Everyone smoked inside then, ears matching red from another brutal, lonely Fall. As required, Eva went while menstruating so that her cervix would be dilated, and the Dalkon Shield easier to implant.

“Take out your Tampax and wait for the doctor,” the receptionist said, also Puerto Rican. She left Eva in that emblematic cubicle that the sick can never escape and the well only recall on sight.

At that time the clinic seemed worn but never dangerous. It needed paint and was crowded, like the rest of the city. Later, people born in the suburbs would move to Manhattan. There, they would recreate the culture of gated communities, trading freedom for security. The social contract would expire, and this clinic’s budget would be slashed, its hours reduced. Finally, as gentrification scattered its constituency, the building was closed down entirely and not replaced. The services were never duplicated. The specter of AIDS overrode everyone’s anxiety about syphilis. Many former clients died, poised vaguely in someone else’s memory. But on that drippy day, this future was unpredictable. If Eva had asked the others on line what kind of future they expected, most of her fellow New Yorkers would have predicted more of the same or some improvement. That about sums up the innocent seventies.

Following instructions, our gal carefully wrapped her Tampax in Kleenex and took out a waterlogged copy of Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, required reading for Senior English. As the time passed, Eva began to worry that she might start to bleed.

Twenty minutes later, the anxiety was unbearable, then finally justified, as the inevitable bleeding did occur – clots falling off the walls of her young, spotless uterus.

Sephardic Literature: The Real Hidden Legacy

David Shasha

plus Jordan Elgrably on the Sephardic Intellectual

Guilt and Groundedness

Jay Michaelson

David: The Original Drama King

Dan Friedman

The Doctor

Sarah Schulman

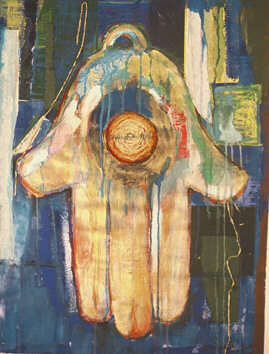

After sepia photographs

Hila Ratzabi

A War in Postcards

Alon K. Raab

Archive

Our 760 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Summer 2005 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

Limited Time Offer

Two years of Zeek in

print for only $20.

Offer expires 9/30.

Click this button

to purchase:

From previous issues:

Much Ado on 2nd Avenue

We Will Destroy the Museums

What, me Tremble?

Leah Koenig

Dan Friedman

Jonathan Vatner