Beyond Belief

Beyond Belief

Reviewed:

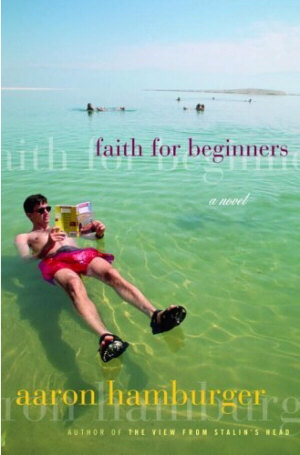

Aaron Hamburger, Faith for Beginners

Random House, 2005. 352 pp. $23.95

When the words 'faith' and 'belief' are used in the context of religion, the distinctions between them tend to blur. People say “I have faith in a higher power that leads me through my living days.” They say, “I believe in God.” And, for most people, these two statements largely mean the same thing. But the differences are essential.

Faith generally means trust without proof, a trust that admits the possibility of skepticism. It contains sorrow and sacrifice and an acknowledgement that—though its effects on the individual are profound—its material value is zero. Faith is for the humble, for those who recognize the infinitesimal meaning of their lives in the greater scheme of the world. Faith, in other words, is active, modest and private.

Belief, at its best, is an assertion of faith. It is the starting point for what might become faith, a cry to the heavens, or to the earthly bodies that promise passage there—please, lead me out of confusion, tell me what to think. At its worst, it implies a lesser, more wishful engagement with the unknown. One can believe in a religious doctrine without ever grappling with the implication of this belief on ones own life; many people do. Belief can be controlled and twisted. It does not allow introspection, because it’s too fragile to withstand contradiction. Belief is an attempt to deny, with a stubborn arrogance, the mortal fear that clots the soul.

Aaron Hamburger understands this.

His first novel, Faith for Beginners, is crammed with people who know what they believe, if not necessarily why. There are the 251 “Michiganders” (Hamburger’s word for Michigan natives) whose slog through Israel on a two-week packaged mission that plays to both their sentimental notions of the “Holy Land” and their desires to be transformed by it, provides the occasion for the story. They are abetted officially by over-excited tour guides, whose every utterance is grounded in the treacly rhetoric of wish fulfillment, and unofficially by puffed-up do-gooders on a mission to save the lost Jewish kids of the world through free meals, free housing and free classes on topics such as “Genesis and the Big Bang” and “A Taste of Talmud.” And since Hamburger is skeptical about nearly everything his characters encounter in Israel, there is Jerusalem’s community of orthodox Jews, who all seem to have abandoned secular lives in America and are now firmly secure in their strict regimen of religious taboos.

If this sounds like satire, that’s because it is. Hamburger can’t resist teasing out the jokes: the lecherous rabbi has to be excessively hirsute; the Yeshiva boy struggling with his homosexuality has to have a stutter. Here’s Hamburger’s description of the leftist rabbinic intern who accompanies the Michiganders on their mission:

| Her basics weren’t bad: dark, smooth hair (a bit puffy) and great big cryptic black eyes, which unfortunately she hid behind black schoolmarmish glasses that clashed with her doughy white cheeks. But how she dressed! That night, for example, she’d chosen a baggy wrinkled dress sewn out of cheap crepe, the color of a sour pickle. This extraordinary uniform was topped off by a yarmulke embroidered with images of children of all different colors holding hands. |

Funny? Yes. But sometimes a bit much.

What saves Faith for Beginners from mean-spiritedness—and reveals Hamburger to be after something more than mere social comedy—is the strength of its two central characters, Helen Michaelson and her son Jeremy [no relation to our chief editor and, according to Hamburger, neither inspired by nor drawn from him! -ed.]. For the most part, the story alternates between their points of view, and both are drawn so vividly and with such complexity that the reader quickly comes to understand that there are real human emotions at stake. What appears at first to be easy mockery of the rubes turns out to in fact be a narrative tactic designed to create a context for the Michaelson’s struggles. The folly exhibited in the minor characters’ eagerness for something, anything to believe will be juxtaposed by the end of the book against the Michaelsons’ struggles toward the more difficult, and profound, attainment of faith.

The Old/New Jewish Culture

Mordecai Drache

Brodsky Begins

Adam Mansbach

A JuBu's Passage to India

Rachel Barenblat

Hitler and God

Jay Michaelson

Winter Light Promises

Jacob Staub

Beyond Belief

Joshua Furst

Archive

Our 820 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Subscribe now!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

The Wheel World

Heart of Pinkness

Wrestling with Installation Art

Dan Friedman

Michael Kuratin

Michael Shurkin