“Sarah?” Andy called up a few minutes later.

He was right. My absence from the table would cast a pall. For ten years, since Jonathan was four, I’ve been draping the kitchen table with a white, plastic table cloth on Friday nights, trying to mark the Sabbath. I serve a simple version of a Sabbath dinner, baked chicken, challah, the Sabbath bread, grape juice and wine. I say the blessing over the Sabbath candles, Andy and the boys say blessings for the wine and challah. For many years I wondered what we were accomplishing. The younger boys ignored the traditional food, and instead ate cheerios, bananas and fruit roll-ups. And five minutes after we sat down, they were done and gone, leaving a smorgasbord of sticky apple juice and soggy cheerios on the floor. Recently, on a Friday night when Andy was out of town, I had skipped the cooking, setting the table and saying the blessings.

“Why isn’t the white table cloth on the table?” my eight-year-old asked that night, before dinner.

“From now on will you do it even when Daddy isn’t home?” begged Joseph, my vegetarian who substitutes two baked potatoes for his piece of chicken.

It was happening more and more. My boys were running with the momentum when I couldn’t. The normalcy of my being at the table tonight would set them at ease. After dinner I could crawl back into bed and resume my inactivity. So I wrapped my fleece bathrobe around me and clomped into the kitchen in my clogs.

When they saw me, the boys hushed in their seats and their lips curved into little smiles.

“Hi Mama,” Andy greeted me cheerfully, as if I had waltzed in. He was standing by the table, forking the baked chicken from its pan to the plates.

“There are the matches,” he said, pointing with the fork to a match box by my plate.

Andy had placed the Sabbath candles in the center of the table, and he was waiting for me to light them and say the blessing. The boys watched to see what I was going to do. Remembering what had drawn me downstairs in the first place, I fought the urge to sit down, and instead picked up the matches. I lit the two candles, and postured myself, palms turned inward, hands covering my face, in the traditional candle lighting position.

“Baruch ata, adonai,” I began, stiffening my fingers and pressing the tips around the perimeter of my face, and supporting my heavy head with finger stilts. I squeezed my eyes shut. When I finished, I was frozen in position, my head resting on my raised hands. Darting rays of multi-colored lights pierced the blackness that filled my head. I wanted to stay in that position forever.

“Good Shabbos,” I said, finally breaking my trance and stepping around the table to give each son and then Andy a kiss.

I didn’t say or eat much at dinner. Andy talked a little about Whiskers. Eventually I retreated toward my bed. I lumbered up the stairs, holding the wrought iron banister to help me pull my weight. The relief of making it though the day buoyed me a little. But tomorrow would be longer. And if I made it through tomorrow there’d be a day after that and still another after that one. And if I was ever able to lift myself up and move forward, my mother’s pathology would flare at me, again. I was tired. Tired by my churning. Tired by hopelessness.

I trudged into the bathroom to brush my teeth. The bathroom was cold and looking into the mirror above the sink, I wondered if my face’s pallid tint was due to the bathroom’s avocado green tiles. I picked up my toothbrush. One more hurdle and I was done. I dotted the toothbrush with toothpaste and raised it to my bared teeth.

“Mommy, I already know by heart two blessings for my bar mitzvah. Do you want to hear them?” Joseph asked, posing himself at the bathroom door. His lips turned up in a tentative smile and he was shifting his weight from leg to leg, probably wondering if I was going to chase him out.

Strangers, often artists and fashion connoisseurs, have been commenting to me about Joseph’s Mediterranean beauty since his stroller days. The saturated richness of his olive skin and dark, wavy hair transcended the glare of the unforgiving fluorescent light emanating from the closet behind him. I compared this perky boy, holding his blue bar mitzvah workbook rolled up in one hand, with the boy who two or three hours earlier at the vet’s had thrust his shaking body into my arms.

“Uh, huh,” I gargled, wondering how he had propelled himself into his room after dinner on a Friday night - a Friday night of a traumatic day no less - to study for a bar mitzvah that at nine months in the future was a lifetime away.

A few years earlier when Jonathan had been studying for his bar mitzvah, he sang me his part only once, a few weeks before the actual service. “You need to go slower and annunciate more clearly,” I had told him. His shoulders slumped and his mouth fell open; I had destroyed what should have been a proud, shared moment for both of us.

I have so often behaved with my boys in ways I later regretted. Like when Jonathan was five and told me midway into the ten-minute drive to school that he’d forgotten his lunchbox. I stopped the car and turned toward him, and then I yelled and yelled. And when I was finished I apologized and apologized. Two weeks after that incident, I had my first sessions with a psychotherapist. “I don’t want to do to my kids what my parents did to me,” I said when she asked what had prompted me to make an appointment. “Tell me about your mother,” she said. There hasn’t been a pause since.

I have so often behaved with my boys in ways I later regretted. Like when Jonathan was five and told me midway into the ten-minute drive to school that he’d forgotten his lunchbox. I stopped the car and turned toward him, and then I yelled and yelled. And when I was finished I apologized and apologized. Two weeks after that incident, I had my first sessions with a psychotherapist. “I don’t want to do to my kids what my parents did to me,” I said when she asked what had prompted me to make an appointment. “Tell me about your mother,” she said. There hasn’t been a pause since.

So if Joseph had wanted to sing me his part on an ordinary night, I might have told him to wait until I was finished brushing my teeth, or until I was in bed, knowing that probably we’d both forget. But the night Whiskers died, a motherly instinct guided me. I couldn’t bring back Whiskers, but I could listen to Joseph sing.

Pulling back his shoulders and lifting up his head, Joseph took position in the bathroom threshold. “Baruch ata adonai,” he began, looking me in the eyes. And a smile spread across his face. I lowered the toothbrush from my mouth, swallowed the toothpaste, and leaned on the sink. His voice was so sweet. I didn’t feel the grit of the toothpaste lining my teeth, or notice the nauseating reflection of the bathroom’s green tiles. A beam of light seemed to stretch from the ceiling and wrap around my son.

I had never heard these melodies outside of the comfort of the synagogue, and leaning against the sink in my bathrobe, looking down at my singing son, I felt transported there. I was exhilarated by the splendor of Torah scrolls glistening in their silver and gold ornaments, and warmed by the rich hues of the sanctuary’s sun-soaked stained glass windows. But most of all I felt the serenity of being together in the sanctuary with my husband and three sons.

The glaring image of my mother that had been in the foreground of my mind faded, and the mass of futility that had been suffocating me began to shrink. I imagined Joseph in nine months, on the morning of his bar mitzvah, and I wondered at his transformation from the newborn bag of reflexes I had once carried home from the hospital, to the son up on the bimah. The son who had come to my bathroom and sung poetry one sad Friday night.

A bereaved mother, a rabbi, and a therapist look at dark emotions

December, 2004

December, 2004

November, 2004

November, 2004

Jonathan Caouette's art-house smash

November, 2004

August, 2004

June, 2004

March, 2004

October, 2003

Constitutive ritual for distributed families

May, 2003

New York, full of life, a cure for loneliness.

June, 2002

Guilt Envy

Dan Friedman & David Zellnik

When Dialogue Harms

Jay Michaelson

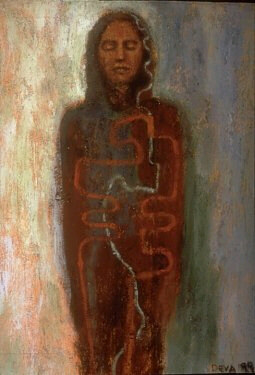

Friday Night Poetry

Sarah Cooper

Tribal Lessons:

A Jewish Perspective on the Museum of the American Indian

Michael Shurkin,

with Esther Nussbaum on Yad Vashem

What, me Tremble?

Jonathan Vatner on Mentsh

Interview

Zachary Greenwald

Archive

Our 670 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Spring 2005 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Harvard Death Fugue:

The Exploitation of Bruno Schultz

Prof. James Russell

Sufganiyot

Rachel Barenblat

The Pursuit of Justice

Emily Rosenberg

Email us your comments

Email us your comments