As every visitor to the country knows, India is complicated. And so was my reaction to it. The Jew in me wanted to rail against the injustices bequeathed by colonialism; the Buddhist in me wanted to sit with the place’s contradictions. The Jew in me wanted to intellectualize, to read more, to tussle with the mental challenges the experience posed; the Buddhist in me wanted to experience everything that came my way without judgment, to merely be mindful of the fullness of the journey.

“Merely be mindful” -- as though that were easy. It isn’t, of course. That’s one of the best lessons travel always teaches (even if I inevitably seem to lose sight of it once I’m home again): just being present in a new place requires all of one’s energy, stretches one in unexpected ways. The same could be said about sitting meditation, or about deep davvening. Immersion is a full-body experience. That’s what makes it worth doing.

Perhaps predictably, the most powerful and memorable encounters with India emerged in the margins, outside of what we’d planned for. The town of Osian is a perfect example. Osian wasn’t on our mental map of Rajasthan, and we hadn’t given our driver any instructions beyond getting us safely to the Thar desert outpost of Jaisalmer. At first, that's just what he did, and we spent a few hours glued to the windows of our old white Ambassador, marveling at the scrub desert, the men in pink turbans, the marigold-sellers. But then our car came to an unexpected stop.

Perhaps predictably, the most powerful and memorable encounters with India emerged in the margins, outside of what we’d planned for. The town of Osian is a perfect example. Osian wasn’t on our mental map of Rajasthan, and we hadn’t given our driver any instructions beyond getting us safely to the Thar desert outpost of Jaisalmer. At first, that's just what he did, and we spent a few hours glued to the windows of our old white Ambassador, marveling at the scrub desert, the men in pink turbans, the marigold-sellers. But then our car came to an unexpected stop.

The town looked pretty typical: dirt streets, cows meandering, camels by the side of the road, bicycles and scooters, bullock-carts, people cooking pakora in great iron woks over little campstoves and open fires. But then we realized that the gateway in front of us led to a long stairway, framed by ornate carved arches garlanded with flowers, with a steady stream of people walking up and down in what felt to me like religious procession. Our driver had brought us to the temple of Sachia Mata.

Entry was free, though we tucked some rupees into the donation jar and took a moment to sign the guestbook. Already that day at least a hundred pilgrims had visited, and ours was the only American address in sight. We moved slowly up flight after flight of stairs, past a boy playing harmonium, past little old ladies who returned our bows and "namastes" with delighted giggles.

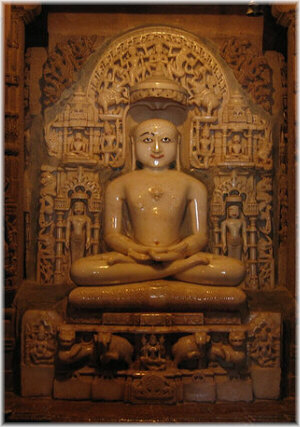

At the top of the stars was the temple's sanctuary, lined with hammered tin and painted mirrors. We joined the queue processing to the inner sanctum, received a forehead-smudge of saffron and a splash of holy water, left a small offering, and perambulated around the room and out to the roof. The exterior of the sanctuary was covered with an ornate frieze of statues: pillars, a procession of figures (deities?) walking or maybe dancing, animals atop animals adorned with elaborate sandstone curls. Like so much else in India, the temple walls told a story I didn’t know enough to understand.

I can understand why many Jews are made profoundly uncomfortable by statues of gods and goddesses. The Judaism we’ve inherited makes much of the Maimonidean insistence that anthropomorphism is inappropriate at best. And though that famous story about Abraham smashing his father’s idols isn’t actually in the Torah, it’s a formative one, usually learned early.

I can understand why many Jews are made profoundly uncomfortable by statues of gods and goddesses. The Judaism we’ve inherited makes much of the Maimonidean insistence that anthropomorphism is inappropriate at best. And though that famous story about Abraham smashing his father’s idols isn’t actually in the Torah, it’s a formative one, usually learned early.

But the statues didn’t trouble me. For one thing, they weren't an attempt at depicting the God of Judaism’s understanding; they’re the crystallization of a whole different story. To me they were opaque, but to believers I imagine they’re useful reminders of human connection with the source of holiness. Seeing them, touching them, might serve the same purpose for Hindu pilgrims that laying tefillin beside the kotel would do for me. I understand our ultimate Source in Judaic terms, but the fact that Sachia Mata is a holy place for somebody makes it relevant to me, even though the prayers offered there differ from my own. I left inspired.

I’d like to be able to say that everything I encountered in India was as uplifting as that visit. But the poverty, as visitors to India also know, is painful. It’s difficult to keep from averting one’s eyes to the shantytowns that stretch for acres, and one naturally feels heartbroken when lepers missing hands or ears or noses plead for money. But after a while the heart seems to harden; what was a raw reminder of human suffering on day one becomes just another disabled beggar seeking rupees by day eight or nine. I lost patience with the gangs of children who poked us, yanked on our arms, and beat at our calves through the open sides of motorized rickshaws stopped in traffic. I didn’t give them money. I tried not to even meet their eyes. And I wondered whether I ought to feel bad about that. I’m still not sure.

Giving tzedakah is a Jewish imperative, and at its root, tzedakah means something like righteousness. (I’m dissatisfied with the standard translation of “charity.” Caritas is giving motivated by mercy and lovingkindness, maybe by what Jewish tradition conceptualizes as chesed; tzedakah is a different thing, motivated out of a sense of justice.) But what constitutes righteousness in this case? I’m American, and thus wealthier than most of those beggars could ever dream of being. Should I therefore empty my pockets? Is it just to give rupees to able-bodied schoolchildren, thereby encouraging them to continue to stay out of school and beg? Is it ever just to turn away? The Jew in me wanted to tithe, but was overwhelmed by demand; the Buddhist in me wanted to remain loving and compassionate, but was overwhelmed by the abrasiveness of the requests. Most days it felt like I was falling down on the job, no matter which religious system I tried to measure my actions by.

I was frustrated, though. We couldn’t enjoy a simple bourgeois pleasure like sitting in a park to read our books, because in addition to the peanut-vendors and the bhel-puri-sellers and the cotton-candy boys (who hassled everyone, Indian or foreigner) we got harassed by girls who wanted to paint me with mehndi, shoe-shiners who wouldn’t take “no” for an answer, and packs of boys who encircled us and demanded funds until we had to get up and walk away. It’s jarring to go to a place intending to be open-hearted, and to realize once there that people couldn’t care less about one’s heart as long as one’s wallet is at their disposal.

On the other hand, many of our encounters were quite memorable. We spent half an hour visiting with a young mustached man named Eldi who employs two friends making cloth- and leather-bound notebooks. We spent a chunk of afternoon at Ganesam, a small silversmithing shop, conversing with Ashok about why women aren’t generally merchants. We bonded with stout Yogi, who sells bedspreads and vests and purses spangled with mirrors, over our mutual “textile addiction.” Each time we came away with a handful of physical items—bright patchwork pillowcases, blank books with flowerpetal pages, earrings to give away on our return home—but even better, we came away having genuinely met someone. Having really meant it when we said, “the light in me greets the light in you.”

Even in such situations, though, there was no escaping awareness of inequality. I turned it over in my mind constantly. Why was this poverty so much harder for me to deal with than the poverty I had encountered elsewhere in the world? Intellectually I was sure that turning away from need wasn’t the right religious response, but emotionally my circuits kept overloading. I didn’t want to be the stereotypical naïve Western tourist, incapable of handling the realities of even a brief visit, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I wasn’t handling the encounter as well as I should have been.

The Old/New Jewish Culture

Mordecai Drache

Brodsky Begins

Adam Mansbach

A JuBu's Passage to India

Rachel Barenblat

Hitler and God

Jay Michaelson

Winter Light Promises

Jacob Staub

Beyond Belief

Joshua Furst

Archive

Our 820 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Subscribe now!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Enraged in the Enron Age

Postcards from Gaza

Shtupping in the Shadow of the Bomb

Dan Friedman

Kitra Cahana

Marissa Pareles