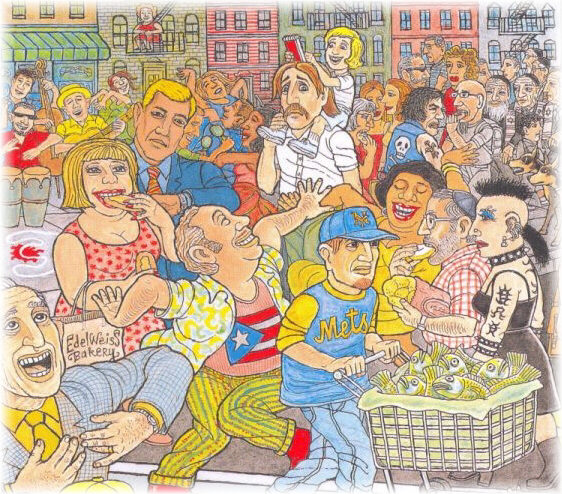

The central problem with gentrification has little to do with New Yorkers' sentimental resistance to change. This resistance is both sentimental and ironic, since New York has been changing ever since New Amsterdam was founded, and in the main, as residents of the primary historical entry point and transitory holding station for America's ever-thickening melting pot, most New Yorkers have learned to accept change anyway. Sure, the neighborhood lifers may grumble about their good old days while the young hipsters grab for the fashionable bits of neighborhood nostalgia. But ultimately they both understand that the neighborhood their parents struggled to establish (or in the case of many hipsters, someone else's parents) will not be the same one their children or grandchildren explore.

The real assault of gentrification has to do, instead, with displacement – both of individual families (who tend to be economically disadvantaged) and, with them, the very idea of distinct neighborhood culture. The model of gentrification that Kurlansky describes in the Lower East Side includes the pushing out lower-income people (in Boogaloo's case, the Latinos and elderly Jews) as a neighborhood gets inhabited by new residents. Of course, in practice, there are actually several intermediate steps. First come the pioneering artists and young idealists who brave the streets' grittiness in exchange for cheap rent. I am one of these. I am writing this review from a peaceful Brooklyn street that was once dominated by blighted buildings and drug dealers. Next, real estate speculators begin jumping in, buying up properties as in Williamsburg and Park Slope, and subsidizing retail stores that they know will make the area suitable for yuppies. Then, shortly after the balance tips, the yuppie "Smarts" swarm in and substantially drive up the property values, leaving many of the neighborhood's residents unable to make rent. (A recent New York Times article, Once Derelict, Now Desirable" describes apartments in the Fort Washington neighborhood that sold for $7500 in the 1980s and are currently listed for as much as $900,000). Finally, as the tenants and businesses in a neighborhood change, the walls in the once modest kosher butcher shop take on new and increasingly upscale identities – greasy spoon diner, artsy coffee shop, sculpture gallery - like layers of paint.

In addition to displacement of individual people and families, gentrifying neighborhoods also face the threat of large-scale identity whitewashing. Nobody but Nathan and perhaps a few loyal customers would weep if he sold his independent copy shop to provide his daughter with a quality education. But the cumulative effect of such individual decisions can be devastating: the annihilation of the concept of neighborhood. A gradual shift from egg cream stands to Nuyorican mango pop carts is one thing. But as the ecology of a neighborhood gives way to a monocrop of Starbucks, Kinkos, and Whole Foods, the neighborhood begins to look, function and – in extreme cases – become interchangeable with any other neighborhood. The neighborhood's standard of living becomes inaccessible to those can no longer afford it, and culturally deadening to those who created the local culture in the first place, as well as those first-wavers who found it inspiring. yuppies are content to consume the culture, especially in quaint, prepackaged forms. But precisely the "authentic" culture the yuppies came to consume is, perversely, destroyed by the yuppies themselves. Meanwhile, first-wave artist types like myself are left to wonder how much we, too, contributed to the destruction of precisely that which we had sought to appreciate.

In addition to displacement of individual people and families, gentrifying neighborhoods also face the threat of large-scale identity whitewashing. Nobody but Nathan and perhaps a few loyal customers would weep if he sold his independent copy shop to provide his daughter with a quality education. But the cumulative effect of such individual decisions can be devastating: the annihilation of the concept of neighborhood. A gradual shift from egg cream stands to Nuyorican mango pop carts is one thing. But as the ecology of a neighborhood gives way to a monocrop of Starbucks, Kinkos, and Whole Foods, the neighborhood begins to look, function and – in extreme cases – become interchangeable with any other neighborhood. The neighborhood's standard of living becomes inaccessible to those can no longer afford it, and culturally deadening to those who created the local culture in the first place, as well as those first-wavers who found it inspiring. yuppies are content to consume the culture, especially in quaint, prepackaged forms. But precisely the "authentic" culture the yuppies came to consume is, perversely, destroyed by the yuppies themselves. Meanwhile, first-wave artist types like myself are left to wonder how much we, too, contributed to the destruction of precisely that which we had sought to appreciate.

Nathan is actually far more privileged than most victims of gentrification. He can sell his copy shop, and get rich. Many residents, though, are squeezed-out by rising rents, and have nothing to show for it other than a bill from the moving company. Then again, it's the market, right? Supply and demand?

At the end of Boogaloo on 2nd Avenue, Kurlansky offers as an epilogue - or maybe epitaph –twelve recipes from the neighborhood. These include two recipes for Sicilian Caponata, Nuyorican Cream Pasteles, original egg creams, and "Karoline's Kugelhopf" – a buttery almond pastry. As I look out my own window today, toward a street where it is increasingly easy to find biscotti and espresso, these lost tastes seem like a fitting zetz in the kishkes.

June, 2005

Walking through The Gates

March, 2005

The Jewish Council on Urban Affairs: An appreciation

March, 2005

How I learned to stop worrying and write a novel about Israel

February, 2005

An interview with the Jews for Racial & Economic Justice Director

October, 2004

Brooklyn's latest hepster yids make good

July, 2004

The Zeek interview

May, 2004

January, 2003

New York, full of life, a cure for loneliness.

June, 2002

Tisha B'Av

David Harris Ebenbach

Postcards from Gaza

Photographs by

Kitra Cahana

Morituri Te Salutant

Ari Belenkiy

The Place of Anger

Fiction by Jay Michaelson

Much Ado on 2nd Avenue

Leah Koenig

Elinor Carucci: Diary of a Dancer

Commentary by Eliot Markell

Archive

Our 730 Back Pages

Zeek in Print

Summer 2005 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

Limited Time Offer

Subscribe now and get

two years of Zeek for

25% off regular price.

Click this button

to purchase:

From previous issues:

I'm Hearing Music from a Different Time

Sounds those Chimes of Freedom

Life During Wartime

Zeek staff

Bex Schwartz

Jay Michaelson

Email us your comments

Email us your comments