Zalman explains the goal of Psalms in a translation for praying: A work in progress, at the outset: "In my work with liturgy I found that when a version was overly faithful to the Hebrew it was good for studying. If it was sonorous and high-sounding it was good for ceremony and high ritual. But to render the psalms as prayers a more direct and more heart-connected version would be better." 'Better' here means facilitating the goal Reb Zalman believes we should have as we recite the Psalms, which he has articulated in his book Gate to the Heart: "Consider in the recitation or singing of the psalms that we are not merely the recipients of their grace, but that we, in turn, send them through us and back to their source. In this complete circuit, we both pray and are prayed, re-creating prayer as we pray." (Gate to the Heart, p. 33) Zalman aims to stand somewhere in the middle, somewhere around the line that separates authenticity in the text-as-received and authenticity in the text-as-experienced.

Zalman explains the goal of Psalms in a translation for praying: A work in progress, at the outset: "In my work with liturgy I found that when a version was overly faithful to the Hebrew it was good for studying. If it was sonorous and high-sounding it was good for ceremony and high ritual. But to render the psalms as prayers a more direct and more heart-connected version would be better." 'Better' here means facilitating the goal Reb Zalman believes we should have as we recite the Psalms, which he has articulated in his book Gate to the Heart: "Consider in the recitation or singing of the psalms that we are not merely the recipients of their grace, but that we, in turn, send them through us and back to their source. In this complete circuit, we both pray and are prayed, re-creating prayer as we pray." (Gate to the Heart, p. 33) Zalman aims to stand somewhere in the middle, somewhere around the line that separates authenticity in the text-as-received and authenticity in the text-as-experienced.

Zalman comes up with some marvelously liberating interpretations. Compare the following lines from Psalm 19. The JPS translation offers:

|

He placed in [the heavens] a tent for the sun, Who is like a groom coming forth from the chamber, Like a hero, eager to run his course. |

Now Zalman:

|

The sun, he is at home in [the Heavens]. And he-the sun-like a proud lover Who comes forth from his tryst Rejoices like a sprinter Speeding on his track. |

This is emblematic of Zalman's style: direct, powerful, colorful. Zalman wants us to experience encountering the Divine in our kishkes and his language has a wonderful penetrating power.

Zalman frequently switches God's gender back and forth between male and female, highlighting the limitations of our language and our thinking about sexuality and its ascription to God. Also, more often than not he addresses God in the second person, as You, even when the Hebrew original is in the third person. Take Psalm 77, for instance. The JPS opens, "I cry aloud to God; I cry to God that He may give ear to me." Who is being addressed here? The reader, who is told that the Psalmist is crying out to God, and is perhaps invited to participate, or comforted in knowing that someone else also wants to cry out to God. But Zalman dispenses with the middleman: "I raise my voice to cry out to You, God. I raised my voice and You gave ear to me." This is good stuff, helpful stuff-it brings the davenner, the person doing the praying, to a much more personalized encounter with God through the text. It is certainly a more comfortable translation for our non-traditional Jew than a traditional translation.

Nevertheless, some of the translations simply don't work. Psalm 96, for example, feels clunky:

|

Sing to Yah a new song. Sing to Yah all the earth Sing to Yah and praise His Name. Of His power and might do proclaim. To the nations tell of God's glorious deeds. How great God is, how strong God is, How nature serves God too. The gods of nations made, Of wood and stone are they- God's presence shines with glorious light. How awesome is God's place. |

Like too many other passages, this just doesn't flow off the tongue very well, and feels like it is pulled down by the Hebrew original. It lacks the authenticity of the text, and doesn't facilitate a sense of authenticity in the davenner either.

Which unveils the elephant question standing behind this entire book: Is it possible to offer a contemporary translation of an ancient work like the Psalms that will really be the kind of vehicle for personal expression and authenticity-in-self that Zalman wants? Fundamentally, even the most liberated translation is still going to take its formal, thematic, and linguistic cues from a text written 2500 years ago in a culture vastly different from our own. Wouldn't it be more worthwhile simply to compose new prayers that speak to us in our own language and idiom? Isn't this search for a synergy of authenticities ultimately an exercise in futility?

I'm not sure Zalman would say no. He closes his introduction by noting, "The range of human experience that the psalms give expression to is the glory of this book." True enough. But that doesn't necessarily make them terrific prayers in translation for the contemporary davenner.

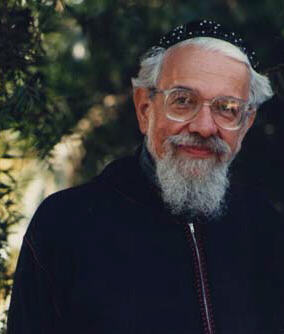

Singing God's Praises:

Psalms and Authenticity

Josh Feigelson

Two Prayers for the Days of Awe

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

How can you be gay and Jewish?

Jay Michaelson

Hiding your Sins

Hal Sirowitz

Retrato de Familia

Bara Sapir

Jews and Bush

An Online Resource Guide

Archive

Our 550 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Spring/Summer 2004 issue now on sale!

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

The Gifts of the German Jews

Michael Shurkin

Hasidism and Homoeroticism

Jay Michaelson