3. Todesfüge

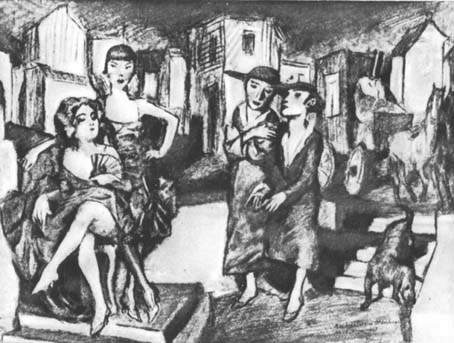

On November 18th, 2003, Harvard University hosted a screening of Bilden Finden (Finding Pictures), a documentary made the young German filmmaker Benjamin Geissler. During the Nazi occupation, Schulz was protected for a time by a Viennese Nazi brute named Landau who fancied himself a patron of culture. (It was a rival of Landau's who casually walked up to Schulz during a razzia and shot him dead at point blank range.) Under Landau's orders, Schulz decorated the bedroom of Landau's small children with frescoes, but after the war nobody knew where they were, or even whether they had survived. Neither the USSR nor the Polish People's Republic wished to claim Schulz anyway; he was popular only in the West. After the Iron Curtain fell, the filmmaker's father, Christian Geissler, set out to find them: Finding Pictures chronicles their discovery, and presents interviews with people in various countries who knew about Schulz- both Holocaust survivors who had been his friends and who were ready to share their memories, and Landau's descendants, who were reticent (at best) about the war. In many ways Finding Pictures is a remarkable documentary, and the discovery of the lost frescoes underneath several layers of postwar whitewash in a pantry, the gradual reappearance under the restorer's careful knife of astonishingly vivid faces, is dramatic in the extreme. I felt the same mixture of tenderness and horror evoked by the portrait frescoes unearthed at ancient Pompeii: one marvels at their consummate skill, one feels the great poignancy of common humanity over the gulf of time, and one is oppressed by the sure knowledge of the impending and total devastation. But they were made not two millennia but sixty years ago, and so one also knows the hideous circumstances of Schulz's creation: while he painted fables for Scharführer Landau's children, Jewish children were being exterminated en masse.

The film captures Christian Geissler's first reaction to the frescoes masterfully: a combination of what seemed to me esthetic delight, awed disbelief, and gut-wrenching sorrow. However, for the remainder of the film -- one might say the whole purpose to which Geissler fils guided it, and the discussion that followed -- was a nauseating abomination.

Shortly after the discovery of the frescoes, three representatives of Yad Vashem quietly travelled to Drohobycz, paid off various people, and cut most of the paintings down from the wall, leaving fragments. In an operation reminiscent in some ways of the kidnapping of Eichmann from Argentina, they spirited their fragile, bulky trove out of the Ukraine and to Israel, where they are now. The latter part of the film deals with these developments and the controversy surrounding them. Certainly, Yad Vashem's actions seem dubious at first. But context is critical. The ruined synagogue of Drohobycz had been the target of four firebombings in the 1990's - this is mentioned in the film - and it is well known that the western Ukraine has been for decades a center of ultra-nationalism. A statue of the fascist murder of Bendera has been erected there, since the disappearance of Soviet rule. (The Soviets themselves named a town after the 17th-century mass murderer of Jews, Bogdan Khmelnitsky, and a big statue of the scoundrel stands in the center of Kiev.)

There are only a handful of Jews, all elderly, left in the town. Presumably the directors of Yad Vashem decided that the frescoes, irreplaceable relics of the last, terrible days of Galician Jewry and of one of its most illustrious sons, would not only be largely unseen, were they to remain where they had been made: they would be unsafe as well.

There are only a handful of Jews, all elderly, left in the town. Presumably the directors of Yad Vashem decided that the frescoes, irreplaceable relics of the last, terrible days of Galician Jewry and of one of its most illustrious sons, would not only be largely unseen, were they to remain where they had been made: they would be unsafe as well.

But Benjamin Geissler's film presents Yad Vashem's act as an unmitigated act of vandalism. It is made to be the worst episode of the tragedy, a crowning act of duplicity- against history, against art. The director opined that, had the murals stayed in the Ukraine, Schulz would have remained living and contextualized. In Jerusalem, he becomes just another dead Jew. Others were to return to this theme in the discussion. I lived for half a year in the neighborhood of Bayit Vegan, a five-minute walk from Yad Vashem, but I would never have recognized the place from Geissler's footage of the Jerusalem museum: almost all the viewer sees of it is smoke from a burning rubbish heap in the foreground, with dusty scraps of roofing fouling the landscape beyond and a helicopter ominously roaring across the background. The inhabitants of this wasteland are highlighted, too: a fat woman tourist in a very American-looking, gaudy dress. Geissler does not film the archives or exhibits of the museum, its conservation labs, the methods of display and preservation of the frescoes, their explanation to visitors. (The only other footage of outdoor Jerusalem is a long, gorgeous shot of the Old City skyline centered on the Dome of the Rock, with the Muslim call to prayer on the soundtrack. So the Arab part of town, as it were, is gemütlich; the Jewish ghetto, schrecklich.) By contrast the scenes of Drohobycz are gentle, soulful, snowy.

Several aged Jews are found to decry Yad Vashem's policy in interviews, though it seems a few approved of it at first, and had to be prodded to disavow it. I noticed all the Jews in this film are old. Perhaps that is because the survivors are old. Yet the Nazi Landau is shown, repeatedly, in a photograph where he is young, and strong, mounted on a spirited white horse. What a contrast! I could not help feeling that the director seemed to like Jews if they are suitably old and gnarled, in what seems like a reflex of the age-old anti-Semitic stereotype of the Wandering Jews condemned to a permanent and preternatural decrepitude. Am I being paranoid? Perhaps not, for during the discussion after the screening Geissler said how much he disliked seeing Israeli kids at Yad Vashem, "eating their hamburgers." Those were the first living Jewish children mentioned all evening, and they were evoked with supercilious disgust. Their sin seems to be two-fold. First, these children dare to be happy, hungry, and boisterous, like human children- instead of haunted, meek, anxious, like good Ghetto Jews. Second, in Geissler's fantasy it is not falafels they are eating, but hamburgers, the vulgar junk food of arrogant America,

As to the other children, the children of wartime, the nightmare setting of the frescoes is somehow smoothed over: there are Nazi children (Landau's, enjoying their nursery paintings and now claiming to know nothing, to remember nothing) and Jewish children, muses the narrator, but they are all children. If such an equivalence for the year 1942 can truly be entertained, then surely the stance of moral relativism has entirely exhausted what little usefulness it might have possessed.

Harvard Death Fugue

On the Exploitation of Bruno Schulz

James Russell

The Jews of Istanbul

Sara Liss

The Truth about the Rosenbergs

Joel Stanley

Thinking despite Doubt, Feeling despite Truth

Jay Michaelson

Two Rituals

Joshua Bolton

Hepster Advice

Jennifer Blowdryer

Josh Goes to the Hospital

Josh Ring

Archive

Our 400 Back Pages

Saddies

David Stromberg

Zeek in Print

Winter 03 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Events

Contact Us

Links

From previous issues:

Holocaust Video Testimonies

Dan Friedman

Cheap Jews try to Save the World

Jay Michaelson

Radical Evil

Michael Shurkin