The fruit, rice mixture and flower petals were then distributed on paper plates to everyone. First Mr. Galsurkar recited the traditional blessing on smelling sweet spices and we all sniffed our rose petals. Then came the blessings over the fruit of the tree and the ground, and we ate accordingly. Finally came the blessing on grains and we savored the almost candied rice concoction (like fruitbread but in a far more palatable base). The distribution of these sacramentalized delicacies reminded me of the Temple’s sacrificial meals, though the forms here seemed to be a blend of Jewish and Hindu religious practices. Mr. Abraham invited the guests to come up to fill plates with the actual meal. After the dining and public introductions Mr. Abraham pronounced a mi-shebeirach on each of the givers of thanks.

An uncanny feeling of familiarity struck me throughout the day. Children ran around, stomping too loudly or screaming at inopportune moments. Mr. Abraham frequently shushed both children and adults in order to focus attention. The public introductions were very cute. Many reeled off the number and age of their children, and emphasized the latters’ professional accomplishments with evident pride. Certainly this reflected the need to catch others up on news, but the motivation stemmed from deeper psychic needs. After Eshkol, handsome a young Indian man seated next to me with whom I’d been chatting, introduced himself, George Abraham added some vital data from the dais -- as he did with others -- such as Eshkol’s prominent descent from a stalwart family back in Thane, near Bombay. When the woman across the table heard this, she exclaimed to him out loud in pleasant surprise, “Your mother is my mother’s best friend!” (They later sat together and schmoozed). The remarks of Mr. Abraham and the tall, stately Romiel Daniel, two of the senior members and prayer leaders, repeatedly returned to the theme of inviting the younger generation to participate in communal religious and cultural affairs and to learn the traditions in order to carry them forward. What struck me, an outsider, as sweet and heimish, may not have been so perceived by all. My artist friend, who came with her mother and daughter, rolled her eyes at me a few times. But even this alienation came across as touching (clearly I am not the one who suffers

when my own community’s idiosyncracies on public display).

An uncanny feeling of familiarity struck me throughout the day. Children ran around, stomping too loudly or screaming at inopportune moments. Mr. Abraham frequently shushed both children and adults in order to focus attention. The public introductions were very cute. Many reeled off the number and age of their children, and emphasized the latters’ professional accomplishments with evident pride. Certainly this reflected the need to catch others up on news, but the motivation stemmed from deeper psychic needs. After Eshkol, handsome a young Indian man seated next to me with whom I’d been chatting, introduced himself, George Abraham added some vital data from the dais -- as he did with others -- such as Eshkol’s prominent descent from a stalwart family back in Thane, near Bombay. When the woman across the table heard this, she exclaimed to him out loud in pleasant surprise, “Your mother is my mother’s best friend!” (They later sat together and schmoozed). The remarks of Mr. Abraham and the tall, stately Romiel Daniel, two of the senior members and prayer leaders, repeatedly returned to the theme of inviting the younger generation to participate in communal religious and cultural affairs and to learn the traditions in order to carry them forward. What struck me, an outsider, as sweet and heimish, may not have been so perceived by all. My artist friend, who came with her mother and daughter, rolled her eyes at me a few times. But even this alienation came across as touching (clearly I am not the one who suffers

when my own community’s idiosyncracies on public display).

Even the hoariest tradition is never static, and Eshkol pointed out that what I saw today did not reflect the way things were done in India. For one thing, women would never have read prayers aloud, and the menu was often Western: pretzels and potato chips along with the traditional sweet round pastry pedas, sodas as the only available beverage, and a main course brought in from a glatt kosher Chinese restaurant. It was clear that modernity had not passed over Indian Jewry any less than it had the lands of Ashkenaz. One Indian spouse announced that he was not Jewish, another spouse seemed decidedly Russian, while yet another had all the hallmarks of being a non-Indian Chabadnik. I recalled Florence’s explanation that the Bnei Israel who came to the U.S. came in pursuit of higher education and economic opportunity.

Eshkol’s story itself bespeaks some of the forces at work as this community navigates its new environment. Eshkol’s parents, both Bnei Israel, taught Hebrew in Bombay, and had studied pedagogy in Israel. Having visited a Yeshiva University graduation ceremony in the 1970s on a visit to New York, Eshkol’s father swore that his children would attend the school, despite the fact that he had no children at the time. Both Eshkol and his sister later attended Y.U. Eshkol bore his experience there with good humor and equanimity, as well as his short stint before school at a yeshiva in Monsey, lunching for shabbat at the house of a local Satmar hasid, exploring the shul of the Belz hasidic community, and even enjoying a visit to New Square, an insular Hasidic community that makes Monsey seem downright heterodox. Romiel Daniel, one of the organizers of the Bnei Israel High Holiday services in New York, studied chazanut (Ashkenazic, of course) at Y.U. and conducts services at a synagogue in Queens. Given that Mr. Daniel speaks with a wonderfully thick Indian accent, I queried him further and he confessed that when necessary his Hebrew pronunciation undergoes a remarkable and complete transformation to “shabbos,” “oohs” as Yiddish “oys” -- the works. Like Eshkol, he seemed to accept these cultural contortions with healthy bemusement. Ethnographers all of us.

The polyglot nature of Jewishness, both hidden and revealed, global and local, emerged even more strongly as I parted company with my hosts. When Lavina Abraham, wife of the master of ceremonies, and fellow co-ordinator of the women’s organization, told me her address, it turned out to be in Riverdale, where I live. I had her write it down, so my wife and I could invite them over for a shabbat meal, and mentioned that I had just moved back to the neighborhood but had grown up there and attended the local Jewish school. She asked if I knew her son or daughter and stated their names. Though at first neither name sounded familiar, additional name-dropping yielded the proverbial mental click: of course! those two darker-skinned kids! The Abrahams’ son had been in the same class as my younger sister, their daughter a year behind me. My own daughter, who had ambled over in the meantime, knew the Abrahams’ granddaughter, who studies in her grade in the same school. And to think that as a grade-schooler it never once dawned on me that these kids were anything but Ashkenazic like me.

My wife, upon reading an early draft of this account, commented that the Bnei Israel “sounds more like a community in decay than in formation.” Despite my shock of recognition at her words, I saw as well the efforts -- pleasurable though fragile, light-giving though all too easily lost in the New York din -- of a few demure warriors against the corrosive forces of entropy, diaspora, individualism, spiritual indifference and the banal evil of materialism. Some have dealt with worse: Later that Sunday afternoon, at a housewarming party of some friends, I chatted with an elderly woman who had known me from our synagogue since childhood. She recounted how she retained the most vivid memory of my grandfather’s dvar torah at my Bar Mitzvah, of which I had practically no recollection. “My synagogue was destroyed by the Nazis,” he had said, referring to the Great Synagogue of Hannover where he had presided as rabbi before fleeing Germany with his family in the wake of Kristallnacht. “Who would have thought that now, years later, I would be speaking at the Bar Mitvah of my grandson.” Said this woman, herself from a family of survivors, “I cried listening to him. Everybody cried.” Tears came to my eyes just hearing her; she provided me my own memory.

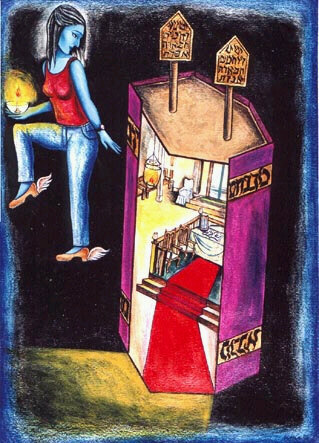

Who is to say what will come of our efforts or those of others? Intrinsic to Jewishness, and perhaps all religious expression, is a form of homesickness, and of others trying to provide us with our own memories. My artist friend, born in India, residing in the United States, wrestles with the complexities of her identity in her work -- Jewish? Indian? woman? modern? traditional? -- juxtaposing jean-clad blue women with six arms against stylized raging oceans; small fires or even mere candles of hopefulness against vast landscapes of darkness and litter. Every one of her paintings contains the same pentagonal shape of a house, usually small, without detail, sometimes featuring within blazing Hebrew letters reading “Shema” or the word “Ima” in classical calligraphy. She called one series of numerous paintings “Finding Home.”

Housewarmings. Burned synagogues. Nostalgia. Selves to be furnished. We will only find home if we look for it or, better yet, build it ourselves. And the prophet Elijah, according to the Zohar, attends our domestic ceremonies and visits our homes as a form of edifying punishment for once doubting that the children of Israel kept the covenant of circumcision -- that is, for doubting that they built the future in the present.

A family of Guatemalan Jewish artists

September, 2004

September, 2004

June, 2004

March, 2004

Toward a postmodern Judaism

August, 2003

Shakey: An Essay on Anger

Jay Michaelson

Giving Thanks to Elijah the Prophet in Indian Manhattan

Jonathan Schorsch

Three Nights

Jill Hammer

The Pursuit of Justice

Emily Rosenberg

Sha'arei Tzedek

Dan Friedman

God's Unchanging Hand

Daniel Cohen

Archive

Our 610 Back Pages

Neurotic Visionaries & Paranoid Jews

April 7, 2005

Zeek in Print

Fall/Winter 2004 issue now on sale

About Zeek

Mailing List

Contact Us

Subscribe

Tech Support

Links

From previous issues:

Sitting on an aeroplane, while Grandma Dies

Nigel Savage

Wrestling with Steve Greenberg

Jay Michaelson

The Mall Balloon-Man Moment of the Spirit

Dan Friedman

Email us your comments

Email us your comments