September 06

September 06

What is Terrorism, and Why We Need to Define It

by Dr. Dan Friedman

p. 2 of 3

Third, this malformation of language is, in a sense, the point of terrorism itself. The point of terrorism is to change the world in which we live, politically and culturally. As Orwell dramatically demonstrates in 1984, the way that these changes are most obviously, tangibly, and immediately manifest is through the language we all use. The transformation of our language is the message that terrorism is sending and our attention to the ethics of linguistic integrity is our first non-controversial anti-terrorist activity.

Finally, the term "terrorism" supposedly refers to a tactic, or an act -- but in fact it is the context which separates a "terrorist" from a "freedom fighter." In our dislike – even hatred – of specific terrorists we often forget how easy it is to like those terrorists with whom we agree, whether they be Guy Fawkes, the Stern Gang, or even, for some on the far left, the Palestinian and Iraqi "resistance" movements. In the Wachowski brothers’ recent V for Vendetta we are strongly encouraged to identify with the eponymous masked militant. The safe marquee names of Hugo Weaving (V) and Natalie Portman (Evey Hammond) seduce us to reassurance with their presence while the science fiction atmosphere of the film obscures the true violence at the core of the film. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist however, and V’s suicide attack on the British minister, however balletically staged, was the deliberate and planned murder of a governing official. V’s crowning glory likewise is the destruction of the Houses of Parliament by a train packed full of explosives. As we try to think about definitions and descriptions of ‘terrorism’ we must remember that they should fit, or accurately distinguish between both V and Al-Qaeda.

Finally, the term "terrorism" supposedly refers to a tactic, or an act -- but in fact it is the context which separates a "terrorist" from a "freedom fighter." In our dislike – even hatred – of specific terrorists we often forget how easy it is to like those terrorists with whom we agree, whether they be Guy Fawkes, the Stern Gang, or even, for some on the far left, the Palestinian and Iraqi "resistance" movements. In the Wachowski brothers’ recent V for Vendetta we are strongly encouraged to identify with the eponymous masked militant. The safe marquee names of Hugo Weaving (V) and Natalie Portman (Evey Hammond) seduce us to reassurance with their presence while the science fiction atmosphere of the film obscures the true violence at the core of the film. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist however, and V’s suicide attack on the British minister, however balletically staged, was the deliberate and planned murder of a governing official. V’s crowning glory likewise is the destruction of the Houses of Parliament by a train packed full of explosives. As we try to think about definitions and descriptions of ‘terrorism’ we must remember that they should fit, or accurately distinguish between both V and Al-Qaeda.

Context, of course, is the difference. Yet context is exactly that which is missing the moral simplifications of defining terrorism. In the rush for the moral high ground all sides have overreached for historical and religious language that will back up their claims. The most obvious example of this has been the mislabeling of this conflict the “War on Terror.” Echoing FDR’s famous phrase “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” it actually betrays the spirit of that statement by focusing on terror, the emotion, as an external, rather than internal, enemy. Moreover, while “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” implies that we should not be frightened of fear, the “War on Terror” implies that we should be terrified of terror.

Nor is the "War" exactly clear. Terrorists are de facto non-nation state actors (even in Iraq and Afghanistan the military actions were taken against illegitimate regimes rather than against the states per se) but, as the linguistics professor James Lakoff points out “[r]eal wars are wars against countries… in the ‘war on terror,’ we are attacking countries. But those countries are not the same as the terrorists. We’re acting at the wrong level.” (http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/08/25_lakoff.shtml) As for whether we're at war, well, my high school students seem to believe that we are in a state of war and even the New Yorker seemed to acquiesce in this media misconception by publishing a series of “life at war” vignettes a few issues ago. It might be a good idea for Presidents to adopt war powers to fight metaphorical wars against poverty, racism, sexual inequality, or drugs but there is as little chance of finally defeating any of those other abstract enemies. Until we know who these ‘terrorists’ are, we will be fighting our own states of mind. As Lakoff succinctly puts it: “There’s no peace treaty with terror.” Terror, then, is its own self-perpetuating war, in which all enemies are labeled terrorists, and thus, in a circuitous and tautological move, all enemies everywhere are terrorists simply because they are enemies.

Finally, victims, too, are often hard to define exactly. In a simple military attack, the casualties are soldiers and they are an accepted, if unfortunate, result of war. In terrorism, there is a spectrum of complicity that is rarely discussed. Troops killed in Iraq after the fall of Saddam and those killed in the attacks of 9/11 or 7/7 are clearly not the same type of target as innocent civilians -- and yet both of these groups are classifiable as victims of terrorism. Indeed, even civilians are not always so "innocent." Saying that oppressed people need to be freed from tyrants (i.e. when the leaders and the people are not identified with one another) implies that peoples in representative countries are responsible for their leaders’ actions (i.e. when leaders and countries are identified). Shareholder responsibilities apply as much, if not more, to national citizens where the stake is in the patria rather than in the company. At the same time as terrorist violence is occurring, destruction is happening on a much larger scale as wars are being prosecuted in our name by nation-states (and environmental destruction is being carried out in the name of shareholder profits). The Nuremberg trials showed that there is a scale of complicity in all regimes – if we define an aspect of ‘terrorism’ as the murder of non-combatants then we need to define and grade the term ‘combatant.’

2. The Media are the Messengers

Terrorism is not a single action like murder or slander, but a complex system of actions. Unlike a military conflict where the action is its own strategic reward, a terrorist event includes a double chain of events. Broadly speaking, the first includes the threat or violence of an attack, and the second its reception by a wider audience. In the first chain someone (a ‘terrorist’) does something (threatens, attacks) to someone else (a “victim”). This action then provides the momentum for the second chain of events, in which something (the news media) does something (reports, comments) to someone else (the audience) who will be changed in some way. This is not to suggest that the news media is a party to terrorism, but we are a necessary link in the chain of events that lead from terrorists to the change they want in their desired audience. Our obligation to report and comment on the events of the world around us comes with a responsibility, because it is the link in the chain of terrorism which transforms the threat or violence into a changed culture of perception.

The first stage of terrorist actions are normally described as being either a “threat” or an “attack” -- or perhaps as being either “verbal” and a “physical” attack. The former is extremely difficult to define and the latter is usually taken for granted. But, as the Weathermen showed in the 1970s, even in the latter category there is an important distinction between attacks on people and attacks on property. Although both are illegal, and despite a centuries-long western fetish for material property, violence to people is clearly, and legally, much worse. Not least because there is, beyond the elite of the global upper-class, a fantastically broad consensus that property is unethically distributed, there is little sympathy for the material (as opposed to symbolic) effects of attacks on property.

The difficulty in discussing the verbal rather than physical attacks is that the use of language as a tool of militancy conflates the first and second chain of terrorism. Although the threat (or sometimes “credible threat”) is aimed at an audience other than the explicitly threatened, the threat itself exclusively symbolic rather than actual. This means we must distinguish between predictions, fictions, precautions, dissensions, and specific threats although they all have similar effects on the final audience. The confusion of these genres has led to unhelpful accusations of betrayal on all sides. For example, as many have noted, the US media (not to mention the government’s National Threat Level) has done an extremely good job of keeping ‘terrorism’ front and centre of its audience’s attention – one of the intentions of the militants. Without a clear generic distinction (or open debate about the distinction) between the “verbal attack” or “threat” and these other forms of public discussion of terrorism, open societies will continue to be embroiled in unseemly, and unhelpful internal bickering leading to that loss of free speech which is another of the militants’ goals.

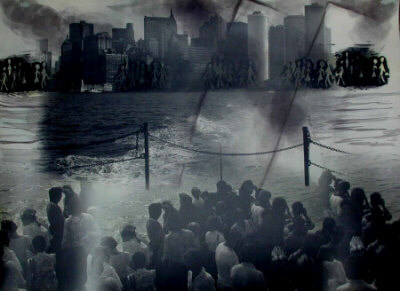

The violence of terrorism is, in part, symbolic. The strength of the symbol is proportional to the outrage it provokes, which comes from the very real pain it causes, but the intention of that pain is always primarily symbolic – aimed at the wider public  who will receive the news and turn it into pressure for change. The second half of the chain of a militant action is how it is received by the public at which it is aimed, rather than the victims who are attacked. This means that the impact of an act of terror is always mediated rather than direct: the target of the violence is never the final target. Al-Qaeda blew up the London Underground (and bus) not because they have an extreme aversion to British public transport but because they wish to prove a larger (if incoherent) point about Islam and post-colonial politics. Likewise, Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Oklahoma federal building was not because he wished to stop those federal employees housed inside from completing any specific tasks but because he wanted to make a symbolic point about the intrusion of the federal government (specifically the Bureau of Firearms, Tobacco and Alcohol) into the lives of U.S. citizens. And in the world of film again, and unlike in a military campaign where troops attack targets for strategic military gain, V blows up the Old Bailey in V for Vendetta because he wants to show that British justice is dead.

who will receive the news and turn it into pressure for change. The second half of the chain of a militant action is how it is received by the public at which it is aimed, rather than the victims who are attacked. This means that the impact of an act of terror is always mediated rather than direct: the target of the violence is never the final target. Al-Qaeda blew up the London Underground (and bus) not because they have an extreme aversion to British public transport but because they wish to prove a larger (if incoherent) point about Islam and post-colonial politics. Likewise, Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Oklahoma federal building was not because he wished to stop those federal employees housed inside from completing any specific tasks but because he wanted to make a symbolic point about the intrusion of the federal government (specifically the Bureau of Firearms, Tobacco and Alcohol) into the lives of U.S. citizens. And in the world of film again, and unlike in a military campaign where troops attack targets for strategic military gain, V blows up the Old Bailey in V for Vendetta because he wants to show that British justice is dead.

In all these atrocities innocents died, and died tragically, but the tragedy of their particular deaths only served to underscore the terrorists’ intention – it could have been anyone who was killed in these attacks. As Gore Vidal pointed out in September 2001’s Vanity Fair, “The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh,” (http://www.geocities.com/gorevidal3000/tim.htm) acts of terrorism are about meaning. We can agree or disagree with Vidal’s description of what he (or anyone) thinks McVeigh (or any terrorist) meant, but the argument should always be about the ideas and symbols involved. Vidal’s comparison of Timothy McVeigh to Paul Revere (also in 2001) is a salutary reminder that not all laws are just and that the line between heroes and villains is not always sharply drawn.

Damien Hirst’s comments on the first anniversary of 9/11 (see this article discussing them in Zeek) pointing out, of the plane attack “that it’s a kind of artwork in its own right” won him a slating in the press but he was, in this case, accurate – and, in context, not even particularly controversial. The attack, he said, “was wicked” but was “devised visually… for this kind of impact.” However incoherent the massage of the attack (and logical coherence is hardly a prerequisite for great art either) the image of the twin towers toppling meant that it was an incoherence searingly felt.