In Clockers, Spike Lee's problem is to make a thought-provoking film about drugs, shooting, and growing up African- American in Brooklyn without glorifying those very things that have such a destructive force on the community. Clockers has been accurately criticized for not having the impact of 'must-see' films like Do the Right Thing, or Jungle Fever - it isn't as good as either of those - but the reason for its lack of 'impact' is that it is dealing with a long-term situation rather than a specific issue (as in Jungle Fever) or a short-term escalation in tension (as in Do the Right Thing). The problem that Clockers addresses is the one of initiating change without replicating the conditions of the trap from which one has just escaped. when there is no movement away from entrenched positions. How does one escape from the ghetto? And, if escape is possible, how does one avoid becoming part of the 'problem' instead of the solution?

It is a well-known fact amongst film scholars, but barely known beyond that

group, that the first ever film was of a train: Arrivée à la Ciotat

by the Lumière brothers (1895)-the arrival of a train from Paris at the resort

town of La Ciotat. I don't know whether this 'fact' is true or not, but it has

the reached the level of truth in the film community, of which Spike

Lee is paid-up member. The main protagonist of Clockers is a young African- American man known to his friends as Strike (although the character's mother named him Ronald) whose hobby, despite the disbelief of his friends and the police who routinely search him, is not basketball but "choo-choo trains." The strangeness of this choice of hobby makes it stand out like a sore thumb in a story of urban ghetto drugs and shooting.

It is a well-known fact amongst film scholars, but barely known beyond that

group, that the first ever film was of a train: Arrivée à la Ciotat

by the Lumière brothers (1895)-the arrival of a train from Paris at the resort

town of La Ciotat. I don't know whether this 'fact' is true or not, but it has

the reached the level of truth in the film community, of which Spike

Lee is paid-up member. The main protagonist of Clockers is a young African- American man known to his friends as Strike (although the character's mother named him Ronald) whose hobby, despite the disbelief of his friends and the police who routinely search him, is not basketball but "choo-choo trains." The strangeness of this choice of hobby makes it stand out like a sore thumb in a story of urban ghetto drugs and shooting.

Strike (played by Mekhi Phifer) cherishes his model train set but has never been on a train other than the subway (think of Spike's early video productions). Strike has videos of trains, T-shirts of train lines, and books of trains but has never bought a single main line train ticket. Eventually, through force of circumstance(the threefold suspicion I mentioned above) Strike has to escape New York. We see him mark his decision to leave by crashing two of his model trains on the layout he has in his apartment, and then in the final scene we see him on a real train heading through the American landscape -- while Tyrone, the twelve-year-old who idolizes him, plays with the model trains that Strike left him, copying, for once, the best of Strike's behaviour.

The trajectory of the film follows the path of the trains in Strike's life. For the vast majority of the film the action loops around and around the same streets in the same urban setting, like the trains going around Strike's model train layout. It is only at the end of the film, once Strike has symbolically crashed his model trains and bought a train ticket out of the city, that the possibility of progress (from Penn Station out into 'America') rather than just movement (round and round the model train layout) exists.

Strike is a smart boy who has been corrupted by Rodney Little (played in menacing Samuel L. Jackson-style by Delroy Lindo). In sweet irony Rodney owns a candy store, which he uses to attract the young men who then operate his crack-dealing business. Strike sells crack, which he knows is evil (and is told so by several upstanding members of his community), but thinks he needs to make the money to help him get where he's going. Although Strike doesn't know where he wants to go, he does know he is sick of being in the frontline for cavity searches, and wants to move up the drug-selling ladder. Rodney tells Strike to 'gat' Darryl-with whom he had once worked at Rodney's shop-as the price for moving up.Without running through the entire plot, Darryl is killed, Strike's brother Victor confesses and Strike is caught between his family, the police, and Rodney all of whom thought that he was smart but now think he is guilty of betrayal.

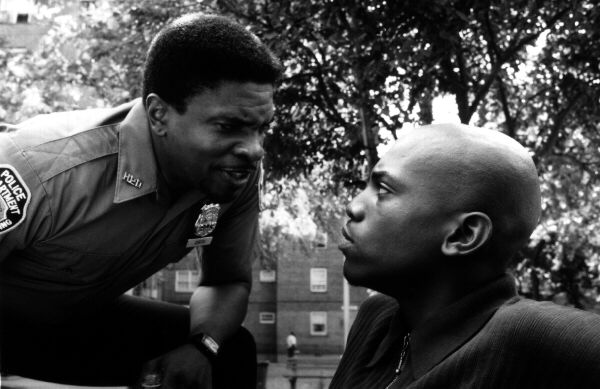

Although there are two strong mothers in the film there is not a single strong father

figure. In fact, the only actual father in the film is Strike's brother-the saintly

Victor Dunham (Isaiah Washington). Even Victor, with glowing recommendations from his

Asian boss, his Hispanic boss, his mother and his wife, can't cope with the strain of

two underpaid jobs and fatherhood, suggesting that the task of fatherhood is impossible

in the ghetto. In the absence of physical fathers the adult males jostle with

one another to provide paternal advice and examples. Rodney treats Strike

as "a son," Strike in turn starts acting paternally towards Tyrone, and

Andre (the giant African American policeman played beautifully by Keith David)

tries to take both Strike and Tyrone under his paternal wing, along

with other neighbourhood boys that we never see, but to whom Andre refers.

Although there are two strong mothers in the film there is not a single strong father

figure. In fact, the only actual father in the film is Strike's brother-the saintly

Victor Dunham (Isaiah Washington). Even Victor, with glowing recommendations from his

Asian boss, his Hispanic boss, his mother and his wife, can't cope with the strain of

two underpaid jobs and fatherhood, suggesting that the task of fatherhood is impossible

in the ghetto. In the absence of physical fathers the adult males jostle with

one another to provide paternal advice and examples. Rodney treats Strike

as "a son," Strike in turn starts acting paternally towards Tyrone, and

Andre (the giant African American policeman played beautifully by Keith David)

tries to take both Strike and Tyrone under his paternal wing, along

with other neighbourhood boys that we never see, but to whom Andre refers.

The possibility of communal progress for the people portrayed in the film is inextricably linked to paternal relationships because it is the actions (and not the words) of the father -figures that are copied by pivotal figures like Strike and Tyrone. These two boys-who have the ability to get somewhere and to take others with them-take their direction from their surrogate fathers, and the 'fathers' fight over their 'sons.' As well as the father -figures within the film, the director Lee (who also appears as a bystander at two of the crime scenes) also feels paternalistic towards Strike. It is no coincidence that 'Strike' is close to being homophonous with 'Spike' because the filmmaker clearly sympathizes with the younger man and fellow tinkerer with trains/films who seems to have had no way out. At the heart of the film is the question of whether Strike will end up like Spike or whether Ronny (the same person) will end up like Rodney.

film politics music jay's head poetry art josh ring saddies about archive