March 08

March 08

ARTSESSION 2007: Contemporary Israeli Artists from Russia

by Marina Genkina

p. 2 of 2

In Israel, minimalism and earth art was the preference. Neither the former nor the latter required the mastery of academic skills. Added to this was the extreme politicization of the Israeli art, which was and is of a leftist leaning, while the Russian-speaking artists’ inclination was mostly to the right.

In Israel, minimalism and earth art was the preference. Neither the former nor the latter required the mastery of academic skills. Added to this was the extreme politicization of the Israeli art, which was and is of a leftist leaning, while the Russian-speaking artists’ inclination was mostly to the right.

The immigrants of the 1970s believed the Zionist dream that the real Promised Land was a purely Jewish land. They believed that they would merge with the glorious family of Jewish artists and would elevate Israeli art to an unprecedented height. They were not prepared for the fact that the Israeli art establishment did not welcome Jewish art – at all.

The 1990s: Creating Israeli-Russian Art

In the 1990s, the number of arriving artists grew immensely, and the situation completely changed in the Soviet Union as well as in Israel. Yet, Russian-speaking artists still found they had to look to the West in order to gain approval from the Israeli art establishment.

By the middle of the 1990s, there were Russian-speaking artists who had reached success with their works abroad, where they sold well. Artists’ financial situation, compared to their initial years, improved and this had a great impact on their self-respect. This is when the Russian-speaking artists took the initiative and viewed the idea of integration into the Israeli art circles as being not only unrealistic but undesirable.

The concept of “Russian” artists has crystallized along these lines: “We are not keen on the idea of locking ourselves in a ghetto; we are willing to accept all artists, including veteran Israeli artists and immigrant artists of other countries, provided that it is we who manage the exhibitions and events. We play by our rules, which include: maintaining a professional level that presupposes mastery of the artistic technique the artist is using, and respecting the profession of the artist. Whoever is willing to accept the rules and show interest will meet the requirements and be more than welcome.”

The following ten years saw the rise of ”Russian" art groups and galleries, mainly in Jerusalem. This catalog traces these Jerusalem artists—with the caveat that there is significant work done during this period by Russian-speaking artists based in Haifa and Tel Aviv. Cataloging that work will be left to future historians.

In Jerusalem, in 1994, an exhibition was organized on the premises of the studio of A. Baratynsky and Alexander Gurevich(two additional exhibitions were organized later), in which several artists, including Sergey Terayev, participated. The exhibition was called “Art Underground Session.” The name is a play on words: the studio is located in a bomb shelter that is under the ground and so it also evokes the idea of the Soviet “underground” exhibitions at which artists presented what they wished and not what they were permitted to show. While the situation in the Soviet Union was one dictated by party politics, in Israel it was and is dictated by the tastes of the art establishment and the art patrons, that is, those who are crucial to the success of an artist. And success did come – even without the help of the establishment. Each exhibition was visited in the first few days by hundreds of people, among them almost as many Israelis as “Russians.”

In the same year as the 1994 exhibition, the “Cultural and Educational Society Teena” was founded in Jerusalem. It’s mission was not exclusively concerned with the arts. It was and is a highly politicized public organization which aims to “demonstrate to immigrants from Russia the advantages and necessities of obtaining peace between the Israelis and Arabs”. Teena also opened a gallery, however, which held solo exhibitions of A. Baratynsky, Benjamin Kletzel, Arkady Livshitz, Vera Shapiro, Julia Shulman, Julia Shulma, and Leonid Zeiger, as well as many group exhibitions.

In 2000, a non-commercial gallery “CoArt” opened in Jerusalem where this writer was an artistic director and curator. The gallery was originally sponsored by funds from “Bracha” and “Yad HaNadiv,” and was open for a year and a half. In that year and a half, thirteen exhibitions were organized. Many of the artists presented in this catalog participated in the exhibitions and, in the case of Benjamin Kletzel and Tania Kornfeld, solo exhibitions were organized for them. The following artists participated in the group exhibitions: A. Baratynsky, Liora Barstein, Galina Bleikh, Anna and Max Epstein, Benjamin Kletzel, Julia Lagus, Menya Litvak, Julia Shulman, and Sergey Terayev.

The gallery was truly conceived not only as an exhibition venue but also as a club for representatives of the artistic intelligentsia where they met during exhibitions, seminars, debates, etc. Its mission reflected the same ideas that were maturing at that time in the Russian-speaking artistic circles, namely: the wall that exists between the artistic circles of veteran Israelis and immigrant artists does not benefit either the former or the latter and it is necessary to at least start chipping at that wall; and, the concept of paternalism with respect to immigrants from the former Soviet Union was to be replaced by the concept of dialogue.

The solution to this problem has not been achieved: the majority of participants in the “CoArt” exhibitions were Russian-speakers. However, something did take root: at the first children’s art exhibition, including the works of students of Russian-speaking teachers, Liora Barstein and Julia Shulman, the works of students of Israeli art schools were also exhibited. There were also solo exhibitions of veteran Israelis organized, which led to lively discussions that went on in spite of the fact that one side did not speak Hebrew very well and the other did not speak Russian at all.

In recent years many artists renewed their connection with Russia. In 2003 the Union of Professional Artists of Israel was formed, largely by Russian-speaking artists. In 2006, Ilya and Tina Bogdanovsky organized the participation of an Israeli group in the 3rd International Biennale of Graphic Art in St Petersburg. More group exhibitions have followed, demonstrating that Russian-speaking Israeli artists are gradually beginning to find a place both in Israel and internationally.

National Identity, Stylistic Diversity

The approaches to painting of the artists in this catalog are totally different: there is the typically Jewish, I would even say Yiddish, humor in pictures by Benjamin Kletzel; the irony and the shock value of many works by Sasha Okun, full of what one might say is sarcastic eroticism; the sharp, “encoded” paintings of Valery Kurov; the meditative landscapes steeped in contemplation of Tania Kornfeld; the worldview of Arkady Livshitz communicated through details – branch, leaves, the trunk of a tree; the cosmic visions emerging in the whirlwinds and spirals of the universe in the world of Julia Lagus; the quiet, nostalgic snow-covered streets of old cities by Joseph Kapelyan; the happiness and joy streaming from the bright multicoloured canvasses of the superb artist, Menya Litvak; the portraits of A. Baratynsky where his family, depicted on old photographs, peer through the torn pixel screen of time; the dynamic water-colour  sketches by Masha Orlovich; and the lyrical, nuanced water-colours of Irina Sorochinsky.

sketches by Masha Orlovich; and the lyrical, nuanced water-colours of Irina Sorochinsky.

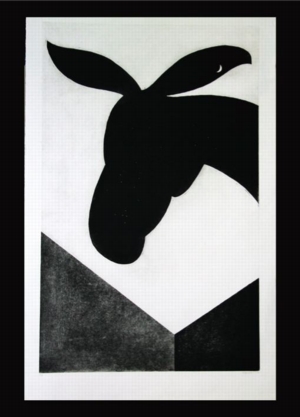

There is also the typical Moscow school, with its attention to the relationship of subtle colours in the works of Julia Shulman; the surrealistic images of Zely Smekhov with his weird horses flying with abandonment through the universe to better, better, better worlds, but without the Okunesque wonderment, and, finally, there are geometrically constructed structures of Goergy Shapira, evoking diagrams of mechanisms where each part has its own place, wherein the pendulum of the clock does not swing but the cog-wheels continue to engage and the clock works.

A great portion of this catalog is devoted to the "Russian" graphic artists. The scope of techniques used by them is very large, from the most contemporary to the traditional. But, as in painting, perhaps even to a greater degree, one observes two different approaches to what is called “the purpose of art.”

The first approach characteristic of the Russian school is to see art as a way of conveying something significant. The series by I. Bogdanovsky is masterfully executed in the etching and aquatint techniques and is titled “Eschatology” while the black and white sheets of Efraim Zaslavski, where the blots, lines and pen strikes form an almost ghostly world that mirrors our own, is one which appears before us but has a different existence; and the mystical graphic art of Anatoly Schelest is done in the monotype technique, a technique so unpredictable that it opens new paths for the artist, not only in art but also in spiritual life, as happened for Anatoly

The second approach follows contemporary post-modernism, which adopts a rule not to lay open one’s “I” but to hide it behind the mask of irony and self-irony, to pretend that both life and art are no more than a game: we can believe in the artist’s viewpoint or not, but that’s exactly where the artist stands.

Julia Shulma, for example, tries to convince us of his utter seriousness. But mystification is also very much present in his works. His graphic sheets, similar to ancient engravings, are, in reality, originals made in ink, and the ceremonial, grand diagrams or the “scientific” Latin inscriptions cannot fool us as to the real intent of the artist. His works represent the post-modernist interpretation of the Moscow conceptualism of the 1970s.

The catalog also features work done in three-dimensional media, including pieces by the designer and publisher of this catalog, M. Rozentov, who presents installations (both already installed and those existing only as models) designed for public buildings and open spaces in streets and town squares.

Next Generation

Most of this catalog covers artists of the middle and older generations. But there are also young artists, born in the 1970s, who came to Israel from the Soviet Union between the ages of fifteen and nineteen and received their education in Israel, at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. From an Israeli viewpoint, the Bezalel Academy is a conservative institution but from the Soviet viewpoint, Bezalel is a western, modernist institution that does not provide proper schooling.

Most of this catalog covers artists of the middle and older generations. But there are also young artists, born in the 1970s, who came to Israel from the Soviet Union between the ages of fifteen and nineteen and received their education in Israel, at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. From an Israeli viewpoint, the Bezalel Academy is a conservative institution but from the Soviet viewpoint, Bezalel is a western, modernist institution that does not provide proper schooling.

On one hand, the young artists are different because they were exposed to Western culture at a very young age – during the formative development period of their personality; for them the issue of the right to free self-expression does not exist, it is self-evident. On the other hand, their ideas are rooted also in Russian-speaking culture because they were brought up on Russian songs, stories, literature, theatre and art. The result is very intriguing – despite their tendency toward irony, the young artists have preserved their dedication to “perfection,” to a high degree of craftsmanship, in the best sense of the word.

Such artists demonstrate that art by Russian-speakers in Israel will continue to grow and evolve.

Marina Genkina is an art critic and historian, born in Moscow and a graduate of the Department of History of Fine Arts at the State University, Moscow. She worked for the Exhibitions Department of the Soviet Ministry of Culture, and was unofficially connected to underground art circles in Moscow and Leningrad. In 1990, she moved to Jerusalem, Israel, and worked at the Library of Art and Archaeology of the Israel Museum (1991 - 2006). She has organized exhibitions in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and was Art Director and Curator of the CoArt Gallery in Jerusalem. Genkina is currently curator of the Skizze-Klub Gallery at the Jerusalem House of Quality.