February 08

February 08

The Doll

Yonah Bahur

|

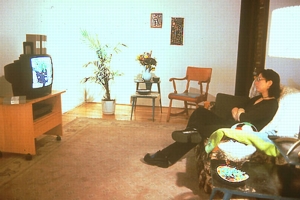

A little more than a year ago, in January 2007, Zeek launched its initiative to publish Hebrew literature in translation. That same month I called up Yaron Golan z”l, publisher and literary critic, to seek his help. I had never met Yaron, and he didn’t know me, yet he invited me to meet him at his apartment one morning in Ramat Aviv. He ushered me inside with slow, deliberate movements, and motioned to me to sit across from him in a living room decorated with paintings, old world furniture, and an array of objets d’art. Just 58 years old, Yaron’s voice faltered as he talked, but a change came over him when he read to me from a volume he had published by renowned Israeli poet David Avidan--he grew animated and his voice filled with life. I had come seeking publication rights to this story, “The Doll,” by Yonah Bahur. Bahur is a mostly forgotten writer whose work Yaron had rescued from obscurity when he published several volumes of her diaries towards the end of her life. I told Yaron that this story seemed to me like a surreal feminist fable; Yaron replied that Bahur’s own life took the form of a tragic fairy tale. He explained that her true love had been killed during Israel’s War of Independence and that she had never recovered from this traumatic loss. Yaron told the story with great empathy that approached reverence. I was to learn later that although he lived a life almost completely given over to reading books, collecting books, publishing books, and writing about books, Yaron always cared more for the people behind the books than the imaginary ones present in them. At that moment, I felt as if he had been waiting for years for someone from America to show up at his door asking to publish some of the literature he loved by the people he cared about. When I left he warmly presented me with a pile of inscribed books. I was probably the last friend he made. The next night Yaron Golan passed away in his sleep. This month’s translation feature is dedicated to his memory and his work - Adam Rovner, Translations Editor

|

A strange thing happened to Michael.

His wife turned into a doll.

It didn't happen all at once.

First the palm of her right hand began to fade. It took on a pale yellow hue like the color of wax, until it became clear that indeed it was wax.

When the disease spread to her other palm, Michael would affix wicks to her wax-plagued fingers on Sabbath eve, light them and prepare to make a blessing over them.

She would stand, her hands raised on high and her lit fingers spread as if in dismay. According to her, she felt no pain.

Once, however, when the wax began to drip on her dress she asked him to extinguish it.

Michael didn't know what to do. Should he or shouldn't he consult a doctor.

Actually, he was afraid to consult a doctor. He was afraid lest it become clear that his wife suffered from some unusual disease. She, on her part, remained indifferent.

She did not demand that they consult a doctor. She spoke little. She stopped hitting the children.

"What's with mother?" the children asked.

"Nothing special," replied Michael. And he even added: "She has a kind of eczema of the hands. You need to show her respect.”

"Mama has eczema," sang the children, and then hid in the closet.

Gradually the disease spread to other parts of her body as well.

The woman began to wear low cut white dresses with long sleeves.

Her palms were covered with black silk gloves.

Frequently, she attended synagogue.

On Yom Kippur, as the family walked together to Kol Nidre services, Michael held the prayer book in one hand and gently supported his wife with the other. And in this way they made their way slowly while the children ran wildly behind them.

At appropriate times Michael and his wife would embrace.

Michael would hold her right elbow, raise her right arm to his left shoulder, and then do the same with her left arm, until her left hand was on his right shoulder.

Finally he drew her close until both her arms and both her hands, now covered in black silk, would slide down his back.

There they would rest.

And thus Michael and his wife would linger for awhile.

Michael grew so accustomed to the new situation that he stopped wondering whether to consult a doctor or not. He was under the impression that this was a natural condition.

She, as she was wont to do, said nothing.

One day Michael noticed that his wife's breasts also took on a pale yellow hue the color of wax. He pressed hard on her chest until a small dimple formed.

Michael asked her if she felt any pain. The woman replied in a whisper that she was never so happy.

Michael painted her breasts in oil paint, one blue and the other red.

As he painted, she said nothing. She only smiled.

"What's with mother?" asked the children. "Why is she so quiet?"

"You need to be good children," said Michael in a threatening tone. “You need to show your mother respect. Don’t bother her."

In a gentler tone he added: "Mother is thinking a lot. She is praying to God for you." The neighbors shunned Michael's house.

"They became such snobs," said the neighbors. "That woman hardly speaks at all, she only smiles and smiles like some kind of know-it-all, and when we try to enter she blocks our way."

Indeed, the woman never stopped smiling.

It was a new development for her.

She sat and smiled. Stood and smiled. Walked to and fro, her back perfectly straight, and smiled.

The children wondered at this additional change in their mother.

They would approach her, tug at the hem of her long white dress, dance around her in a circle and sing: "Mama has eczema... mama has eczema."

She, however, would only smile without stopping and whisper:

"Quiet. Quiet. Quiet."

"Maybe she’s crazy," blurted out one of the children.

Michael hushed him and looked anxiously at his wife.

She kept on smiling.

One morning, as they were relaxing together in their double bed, Michael touched his wife's stomach, and all of a sudden a bleating sound escaped her lips:

"Ma-ma."

Michael removed his hands from her stomach, and the woman fell silent and smiled.

Again he touched her stomach, and the bleating sound came out.

Michael removed her clothes. He removed her clothes and examined her body.

The hue of the skin of her limbs was pale and yellowish, again the color of wax, only her breasts had color, one blue and one red. From then on the woman remained in bed; she lay there motionless.

Michael cared for her devotedly.

He would help her drink small amounts of sweetened milk. He would scrub her body until it gleamed.

Afterward, he would carefully dress her in a nightgown of white silk and cover her palms with long black gloves.

He would fluff up the pillow under her head, gently comb her hair and, from time to time, check the mechanism in her stomach to see if it worked properly.

Michael was amazed that she had no excretions whatsoever.

She was always sparkling clean. It was only due to the love of cleanliness that was in his nature that Michael continued to polish her body, morning in, morning out.

Michael looked at his wife's eyes. They were alive. Quiet and indifferent, but alive. Her mouth twisted in a permanent smile.

It was possible to perceive a dim movement in her lips. But about the nature of her hair, Michael was uncertain.

At times it seemed to him that her hair felt like straw or a wig.

Nonetheless, he didn’t stop combing and brushing her meticulously before he went to work, morning in, morning out.

Michael no longer knew whether she heard his voice and did not respond or whether she didn’t hear his voice and for that reason did not respond.

Her eyes were alive.

At times, out of mischief, the children would steal into the bedroom, feel around in their mother’s white gown and activate the mechanism.

Michael was cross with them. He declared with grave seriousness that God would punish them for the disrespect which they showed their mother.

One day the woman’s eyes were extinguished. They were opened but extinguished.

Michael didn’t know what to do.

He stopped sleeping by her side, but he continued to polish her and brush her hair.

The children propped her up in the corner of the abandoned bedroom and covered her face with the curtain.

Michael didn’t know what to do.

Finally, he decided to invite the Hevra Kadisha, the burial society, so they should bury her according to the laws of Moses.

But they, when they arrived and looked at the doll, refused to bury her for reasons we will not go into.

Michael continued to polish her.

He didn’t know what to do.

One night he was startled. He heard the sound of laughter from the abandoned room. She laughed. She laughed out loud.

He approached her and removed the curtain from her face. Carefully he shut her eyes.

Her laughter ceased.

On the following day the children carried her to a clothing shop in the center of town and left her standing in her white dress and her long black gloves at the entrance.

She faced the street, her eyes shut.

Michael sat shivah.

| Zeek's Hebrew translations are made possible by a grant from the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses, supported by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency. Please direct submissions and queries to editors[at]zeek.net. |

Yonah Bahur (1928-1991) was a writer and critic who is best known for the revealing diaries she kept for over thirty years. Although she had been an intimate of the Bohemian Tel Aviv literary scene, Bahur’s own output was minimal.

Stephen Katz is an Associate Professor of Modern Hebrew Language and Literature at Indiana University, Bloomington. His book, To Be As Others: The Representation of Native- and African Americans in Hebrew Literature, is forthcoming from the University of Texas Press.

.

.