October 07

October 07

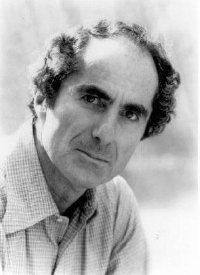

Temporary Like Zuckerman: Philip Roth’s Exit Ghost

Stephen Hazan Arnoff

Reviewed:

Phillip Roth, Exit Ghost

Houghton Mifflin, 2007

Now the word of the Lord came to Nathan Zuckerman – Philip Roth’s counter-life hero in nine novels including the just released Exit Ghost – saying: Go to New York, that great city, and cry against it. Cry against the wickedness that has come up before Me: against your prostate cancer and impotence and trickling urine like a leaky old faucet at the age of seventy-one; against the brain cancer that has left mentor E. I. Lonoff’s former lover Amy Bellette half mad and dying; and more than all else against the people and the politics and the commerce and the ambition of the metropolis where the writer no longer has a living role to play.

No character in the Bible rages like Jonah – challenging death, taunting fate, and baring soul. And no contemporary writer on the American scene is more like Jonah than Philip Roth, pulverizing, memorializing, and scandalizing the nation’s dreams and secrets and gritty absurdities.

“Before death takes you, O take back this” warns the book’s inscription, as Roth’s sharp gaze faces down favorite topics politics and sex, but most especially the matters of aging and dying, which have dominated his work since the early 90s. In many ways Exit Ghost is a direct thematic continuation of 2006’s Everyman, the most recent novel in a decade and a half of furious creation resulting in three PEN/Faulkner Awards and a Pulitzer Prize.

Jumping aboard a ship bound for Tarshish to escape the Lord’s call to prophesy, falling asleep in the hull, inadvertently converting the ship’s sailors to worshipping the Hebrew God, getting chucked into the wild, wide ocean only to be swallowed up by a great fish and held in its belly for three days and nights of kvetching before being spit out on dry land to complete his mission – Jonah cannot stay still for a moment lest he fulfill anyone else’s expectations – even God’s. He assumes unlimited imperfection and messiness in the world, brushing in and out of life buzzing with anger and fatigue.

Jumping aboard a ship bound for Tarshish to escape the Lord’s call to prophesy, falling asleep in the hull, inadvertently converting the ship’s sailors to worshipping the Hebrew God, getting chucked into the wild, wide ocean only to be swallowed up by a great fish and held in its belly for three days and nights of kvetching before being spit out on dry land to complete his mission – Jonah cannot stay still for a moment lest he fulfill anyone else’s expectations – even God’s. He assumes unlimited imperfection and messiness in the world, brushing in and out of life buzzing with anger and fatigue.

Roth claims that Exit Ghost will be seventy-one year old Zuckerman’s last whirl around civilization, and just as Jonah asks time and again for God to relieve him of his misery with the ultimate cure for the messiness of the world, Zuckerman too seems to be begging Roth to give him precisely what death wants to gobble up most. But like Jonah plopped into Nineveh against his will, there is no quick redemption and no merciful death for Zuckerman in Manhattan. Neither creator is willing to let his creation off the hook that easy.

Inside Out You’re Turning Me

Jonah, like Zuckerman, is a loner, a curmudgeon, a perfectionist, and a loyal devotee of the divine element of din – judgment. His name might mean “dove” in Hebrew – a bird symbolizing peace and connection – but as Erich Fromm taught, Jonah lives without love, either human or divine. When called by the Lord to serve notice to Nineveh of its destruction lest it repent, he is flabbergasted by the possibility that the divine element of rachamim – mercy – will generate forgiveness for the cities’ countless trespasses. Riffing on God’s harsh concluding lines to Jonah in the Book of Jonah, Fromm suggests that love is labor and we must labor for what we love. This is a game, perhaps the human game, which Jonah does not want to play, at least not by anyone else’s set of rules. God upends the prophet, who is pouting over the death of a gourd, the castor oil plant that had given him shade before shriveling in the sun before his eyes. Without merciful love binding creator and creation in a “labor of love,” all bets are off, even for God:

And the Lord said: 'Thou hast had pity on the gourd, for which thou hast not labored, neither made it grow, which came up in a night, and perished in a night; and should not I have pity on Nineveh, that great city, wherein are more than six hundred thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand, and also much cattle?'

Until he receives three all expense paid days and nights in the belly of a whale, Jonah completely rejects exposing his ethical shield to being scratched and dented by the  wrangling of life. Then, after he goes through with the job, he is embittered, placing him in familiar, anxious company with both Zuckerman and Roth. Granted, Jonah has a point not wanting to serve Nineveh. One midrash claims that when it had been time for the Ninevites to make good on their vows to repent (and oh how they repent in the end, their goofball king going so far as to call for even the cows in the field to fast and wear sackcloth) all of their houses had fallen to the ground. In returning the loads of goods they had stolen one from the other over the years, they had discovered that even the bricks of buildings where they had lived had been stolen.

wrangling of life. Then, after he goes through with the job, he is embittered, placing him in familiar, anxious company with both Zuckerman and Roth. Granted, Jonah has a point not wanting to serve Nineveh. One midrash claims that when it had been time for the Ninevites to make good on their vows to repent (and oh how they repent in the end, their goofball king going so far as to call for even the cows in the field to fast and wear sackcloth) all of their houses had fallen to the ground. In returning the loads of goods they had stolen one from the other over the years, they had discovered that even the bricks of buildings where they had lived had been stolen.

The Ninevites may seem like slapstick sinners and stooge-like worshippers, but even going through the motions of repentance is more than Jonah is willing to do. While Jonah’s tumultuous narrative embodies the core principles of teshuvah – which literally means turning oneself around and can be translated as “repentance” – and it is read at the poetic, philosophical crossroads leading into the heartrending concluding service of Yom Kippur, Jonah himself never confronts his own foibles and bitterness, remaining aloof on a mountain overlooking the city at stories’ end. Zuckerman has no such luxury of ambivalence, being the very modern creation of a novelist driven by the need to turn his fears and desires inside out for the sake of his art, and, perhaps, for the sake of his own kind of teshuvah.

The No Longers and Not Yets

After eleven years wandering only the terrain of his imagination, isolated deep in the forests of the Berkshires, Zuckerman comes to New York for a collagen treatment for incontinence, a quest for a miraculous partial cure – maybe enough, Zuckerman says, to prevent constant leakage from his swimming trunks during occasional laps in the college pool. Spontaneously initiating plans for a swap of his refuge in the woods for the apartment of a young couple on the Upper West Side, Zuckerman encounters Jamie, a typically underevolved, Rothian vessel of female attraction. She is Zuckerman’s final muse, and he woos her aggressively despite both her being more than forty years his junior and the obstacle of his own impotence. Zuckerman also meets Richard, a young literary predator offering an exaggerated version of Roth or Zuckerman themselves from days long past, primed to explode Lonoff’s anonymity by exposing a family scandal that Zuckerman has vowed to protect. Where Jamie inspires lust, longing, and a kind of love that Zuckerman cannot psychically let alone physically fulfill, Richard inspires cynicism and rage. Both serve as mirrors for Zuckerman’s own exasperation at reentering the world out of the bubble he has created – his ship, his belly of the whale, his removal and resolve against what is too chaotic and painful for the writer to abide.

In his cabin in the woods – or in a mid-town hotel room where he writes He and She, the dramatic narrative within Exit Ghost – Zuckerman chooses a dreamlike routine of writing, walking, swimming, listening to classical music, and watching baseball alone, rather than direct engagement with the world. Let it rot, Zuckerman says, referencing global sicknesses like Al-Quaida and the Bushes as well as personal losses of all sorts. New York, the Nineveh of its time, marks for Zuckerman all that is uncontrollable and real, and, with his body and mind in various states of mortal dysfunction, all that he cannot have. “There is no more worldly in-the-world place than New York,” Zuckerman says,

full of all those people on their cell phones going to restaurants, having affairs, getting jobs, reading the news, being consumed with political emotion, and I’d thought to come back in from where I’d been, to resume residence there reembodied, to take on all the things I’d decided to relinquish – love, desire, quarrels, professional conflict, the whole messy legacy of the past – and instead, as in a speeded-up old movie, I passed through for the briefest moment, only to pull out to come back here. All that happened is that things almost happened, yet I returned as though from some massive happening. I attempted nothing really, for a few days just stood there, replete with frustration, buffeted by the merciless encounter between the ‘no-longers’ and the ‘not-yets.’ That was humbling enough. Now I was back where I needed never be in collision with anyone or be coveting anything or go about being someone, convincing people of this or that and seeking a role in the drama of my times.

Zuckerman discovers that his age, disappointment, and judgment leave him too out of step with the Manhattan hustle to participate in the race further, and so he retreats. But Roth, who is seventy-four, even in hinting that this novel serves as Zuckerman’s final  bow, still keeps on writing, his stream of creativity flowing directly out of the intractable question where both the Book of Jonah and Exit Ghost end: When an artist or prophet – even if it is by proxy, extension, illusion, or happy accident – has been granted the gift of facing death and surviving and encountering and imbibing human corruption without losing the charisma, talent, and drive to change and create, what remains worthy for he or she to say?

bow, still keeps on writing, his stream of creativity flowing directly out of the intractable question where both the Book of Jonah and Exit Ghost end: When an artist or prophet – even if it is by proxy, extension, illusion, or happy accident – has been granted the gift of facing death and surviving and encountering and imbibing human corruption without losing the charisma, talent, and drive to change and create, what remains worthy for he or she to say?

Where Do You Get Your Ideas?

Philip Roth has never been one to provide cutesy, satisfying answers to questions about the source of his work and vision. In fact, Exit Ghost offers a parody of attempts to peek inside the writer’s world, as one of Zuckerman’s neighbors asks him “deadly questions about writing and was not content until I had answered them to his satisfaction. ‘Where do you get your ideas?’ How do you know if an idea is a good idea or a bad idea?’…” and on and on, nearly driving Zuckerman around the bend.

But in thinking about teshuvah in the season of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur along with the lessons of Zuckerman and Jonah read side by side in Jerusalem and New York, the next moment of the Jewish calendar, Sukkot, offers a suggestion about what is left for artists, writers, prophets, and others to say when the wickedness of the world comes up before them.

Ritualizing the shelter of the Israelites wandering in the desert, the sukkah – a simple booth constructed outside of the home for week of celebration as the season of atonement comes to a close, the days get shorter, and the summer and fall give way to winter – is a fusion of protection and exposure and inside and outside at the center of anyone’s world.

Jonah lives in a sukkah near the end of his story, just before the beloved castor oil plant rises and dies and leaves him alone. Temporary like a hotel room, a trial in the belly of a great beast, or a mountain retreat, consider this short novel – even if it is not Roth’s best – as the work of an author who still spares nothing in exposing his characters and readers to even the most brutal weather.

The holiday of Sukkot, unlike any other holiday, legally requires people wishing to observe it properly to be happy. But if winter looms, protection is temporary, and wickedness rises, how can one be commanded to be happy? What could be the source of this joy? Such happiness comes from being that close to the weather, in the belly of creation, where life and fiction and scripture and commentary no longer require definition – and where all of them are made.

Stephen Hazan Arnoff’s essay on Philip Roth’s Everyman was awarded the 2006 Rockower Jewish Press Award for Arts & Criticism. Having served as Contributing and then Managing Editor of Zeek since 2005, he is now Executive Director of the 14th Street Y of the Educational Alliance in New York City.