June 07

June 07

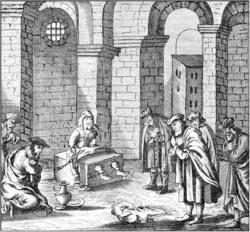

Sabbatai Zevi at Prayer

by David J. Halperin

p. 2 of 2

So, on the eighth day of the month, he dressed his son in fine clothing and went to invite all the city’s dignitaries to his circumcision. They imagined it would take place according to their custom, by which the invitation is issued one day before the circumcision. Yet as soon as he had finished inviting them, he sent immediately for this rabbi [Najara] and ordered him to bring the implements for circumcision. [6]He set up the Chair of Elijah. [7] Then he himself sat on that chair for something like an hour, enwrapped in a mantle, in a state of intense concentration.

So, on the eighth day of the month, he dressed his son in fine clothing and went to invite all the city’s dignitaries to his circumcision. They imagined it would take place according to their custom, by which the invitation is issued one day before the circumcision. Yet as soon as he had finished inviting them, he sent immediately for this rabbi [Najara] and ordered him to bring the implements for circumcision. [6]He set up the Chair of Elijah. [7] Then he himself sat on that chair for something like an hour, enwrapped in a mantle, in a state of intense concentration.

Afterward he rose and made the gentleman Rabbi Joseph Karillo sit as sandak. [8]Amirah recited the blessing, “[Blessed be You, O Lord our God, King of the universe, who sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us] to enter this child into the covenant of Father Abraham” [Talmud, Shabbat 137b]. Then this rabbi [Najara] circumcised the boy. [Sabbatai] recited the blessing of Him “who has kept us alive” and told this rabbi [Najara] to recite the same blessing, having been privileged to perform so pious a deed. This rabbi [Najara] said the blessing of Him “who sanctified the beloved one” [Shabbat 137b] over the wine cup, and the newly circumcised child was given the Jewish name “Israel.”

There was a certain man present, a Jew who had apostatized years earlier, who had a ten-year-old son. The boy had not yet been circumcised, the man having vowed while Amirah was in the “tower of strength” [9] that he would not circumcise his son except in the presence of King Messiah. Amirah thereupon commanded this rabbi [Najara] to circumcise the boy, with the same blessings as before. He was given the name “Ishmael.”

On the Sabbath before Passover [10 Nisan = 21 March], Amirah prayed in the same house in a state of great elation, adding many liturgical poems to the worship service. At the time when the Torah should have been brought forth from the ark, he took out his printed Bible and read from it. The first passage he read was the text beginning, “This is the law of the leper on the day he is purified of his leprosy” [Leviticus 14:2]. [10] He explained this as an allusion to an evil wife, who is “like a leprosy for her husband.” [11] Thus our ancient sages tell us the Messiah’s name is to be “the White One of the master’s house” – which term [“White One”] Rashi glosses as “leper” [Talmud, Sanhedrin 98b].

He went on to read the passage beginning, “In the third month” [Exodus 19:1]. [12] This, he said, was an allusion to its being the third month of his state of illumination. [13] He commanded everyone present to stand up and to hear the Ten Commandments in trembling and dread, for that hour was just like the hour when Israel received the Torah at Mount Sinai.

He then read the entirety of the Torah portion Zav [Leviticus 6:1-8:36], and afterward feasted in great joy. Throughout all this the windows and doors were closed. At the time of the afternoon prayer he opened all the doors and all the windows, and, although a number of Gentiles were watching through the windows and doors, not one of them made any protest. When he came to the Alenu prayer, he told the turban-wearers to recite the prayer in a loud voice along with the Jews, facing eastward as they did so, and to pay no attention to the Gentiles who watched them. Thus they did.

Afterward [Sabbatai] sat down to eat the third meal of the Sabbath. He did not allow any of the turban-wearers to sit with him, but only this rabbi [Najara] and one other Jew. Then he took a full cup of wine in his hand, and he loudly and tunefully sang the hymn that begins, “The sons of the palace who yearn.” [14] This he followed with “A psalm of David, The Lord is my shepherd” [Psalm 23] and the blessing over the wine. Prior to the meal, and during the meal prior to the fruit course, he recited several chapters of tractate Shabbat [of the Mishnah], and the first chapter of tractate Berakhot. Afterward, at the time of the after-dinner grace, he again took a cup of wine in his hand and recited the hymn beginning, “Let us bless Him who sustains all the world.” [15] He then said grace in a loud voice, pronouncing each word distinctly.

That night, at the close of the Sabbath, he recited the evening prayer in a most melodious fashion, and with great joy. Once the Sabbath was done he went riding on a horse, taking with him some thirty of the Faithful Ones who wore the turban. In his hand he carried the jeweled Zohar-book. [16] He went about the city, through the marketplaces and the streets, and all the dignitaries of the empire saw him going about with his troop of followers, the book in his hand. Not one made any protest.

On the first day of the month Iyyar [11 April], about eight men came from Ipsola, and he made them to wear the turban [i.e., converted them to Islam]. On 3 Iyyar he summoned this rabbi [Najara] and said to him: “Be aware that all the tribes I have made before this were part of the mystery of the World of Chaos, the mystery of ‘He built worlds and He destroyed them.’ [17] But now I am canceling all I have done, and now I swear this structure I am building is …”

[Here the text breaks off].

2. The Messiah Prays at Machpelah

(Translated from Abraham Cuenque by David J. Halperin)

At that time a decree was issued in the province of Egypt, and [the leaders of Jerusalem Jewry] did not know where they might turn for help. There was a high official in Egypt named Joseph Raphael, and they pondered whom they might send as their emissary to him.

Sundry proposals were offered. One of the group then said, “If it might be possible for Sabbatai Zevi to go on our mission, God will certainly grant us a favorable outcome. For the noble Joseph Raphael thinks the world of him.”

“But surely he will not agree to it?” they said.

Yet they said, “Whatever may come of it, let us importune him. Perhaps he will agree.”

So all the rabbis, who were at the time both numerous and notable, went and spoke with him. He replied: “I am prepared and ready. Well have you asked; timely have you spoken. I wish to depart this very day. First, however, I should like to go and pray at the cave of Machpelah in the holy city of Hebron.”

“Please,” said they, “spend the night here. Tomorrow you can go with a caravan.”

“No,” he said. “I will leave today. Do not hold me back; the Lord has already granted me success.”

That was what he did. He rode upon a horse, one man going before him, and he came to us [in Hebron] and stayed as guest of that most excellent of the scholars of his generation, the well-born Rabbi Aaron Abun of blessed memory. For so he had requested before entering our sacred precinct, [18] that he should be hosted by that rabbi and only that rabbi.

This was the first time I had seen him. I was a regular visitor to Jerusalem, yet I never saw him until he came to visit us. I was awestruck at how tall he was, like a cedar of Lebanon. His face was very ruddy, a touch inclined toward swarthiness; his features were handsome, encircled by a round black beard; he was dressed in garments truly royal, and was altogether an exceedingly healthy and imposing person. From the moment he entered the sacred precinct – all the time he prayed the afternoon prayer in our synagogue, all the time he prayed the evening prayer in the cave of Machpelah along with the crowd that had flocked after him – I could not take my eyes off him. Nor could the human mind conceive where he might have hidden away all those tears he shed as he prayed, not like natural tears but like a vast flooding, or like streams that rush ever onward.

I spent most of that night in the vicinity of the house where he was staying, and I observed the acts he performed. All the dwellers in the sacred precinct, similarly – men, women, and children alike – found themselves unable to sleep all that night. They spent the night instead watching through the windows, peering through each crack.

He paced hither and thither through his house, which was filled in its entirety with torches, for so he had ordered. Throughout the night, until dawn broke, he recited psalms by heart in a voice that was loud and happy and joyful, most exceedingly pleasant and sweet to the ear. At dawn he went to the synagogue and prayed the morning prayer. I can attest that everything about him was such as to inspire dread, and that, among all the dwellers on this earth, he was in every way unique. I could not get my fill of watching him.

When the morning prayer was finished, about three hours afterward, he set forth by himself in a certain direction. He was accompanied six parasangs [roughly 20 miles] by a Jew who attended him. While he was with us [in Hebron] he did not eat a bite nor did he drink any water, nor did he sleep at all, not so much as a catnap. Fasting he came; fasting he departed. To this day I never saw him again, but only twice in my dreams – one of them in Hebron, the other in the darkness of my exile.

David J. Halperin is Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. From 1976 through 2000, he taught the history of Judaism in the UNC Department of Religious Studies, where he was repeatedly recognized for excellence in undergraduate teaching. He is the author of five books, the most recent of which, Sabbatai Zevi: Testimonies to a Fallen Messiah, will be published this month by the Littman Library of Jewish Civilization (Oxford, UK). He lives in Durham, NC, with his wife Rose.