April 07

April 07

Sting: An Excerpt from "Preliminaries"

by S. Yizhar

p. 2 of 2

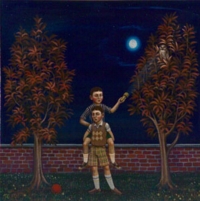

And suddenly and in spasms, as if something inside him is trying to escape, or he cannot cope any more, as if some refusal is working inside him, some resistance from all his tiny being, and Mummy turns to him, and Daddy turns to him, the reins in his hands, his face wrinkled, his hair dusty, unshaven, his shirt sweaty, his arms big and gnarled, with straw on the backs of his big hands holding the reins, turning towards the child and all poured out and leaning, are they three people together here now, or each one alone not knowing what to do, with nothing to hold onto, and shudders go through the child, his blood is poisoned, his veins are nettle-rashed with poison, maybe right to the heart, and can he withstand it, how far has the poison got, and the terrible pain that the fainting absorbs for the time being, and prevents him shrieking, sobbing and flailing with his legs and arms, and writhing with this unbearable pain, what is pain, what makes pain pain, Daddy doesn’t know, Daddy who always knows more than others and always knows because he has always read something once and he never forgets anything he has read, but Daddy does not know what pain is or what happens in someone who has a pain, and this suddenly takes him away from the presence that is fixed on the child and he slinks away for a moment towards the extra knowledge of those who know how to know. What do they know about wasp stings, about the poison, about what it does to a person, let alone a little two-year-old child, so weak and frail, and what did he do to them to drive them mad, why did they suddenly swarm on him and inject venom into him, did he touch them with his little finger in their hole, or push a stick into the hole where their nest was and their babies, where they stood guard against any invader, what is this wasp anyway, what do we know about it, it is written in the Torah ‘And I shall send my hornet before me,’ and it says ‘none of your sting, none of your honey,’ in Midrash Rabbah, apparently, who knows any more about the wasp, this gold-colored bee, the big bee that eats bees, in the underground nest live the queen the workers and the soldiers, and these are the ones that were alarmed and came out in full force to repel the invader, what did he do to them, this invader, what was he capable of doing to them, he put in his hand by the hole, and suddenly Daddy recalls the tale of the maiden of Sodom who gave bread to a poor man and when the act became known they spread honey upon her and exposed her on the wall, and the wasps came and ate her – is it in Tractate Sanhedrin? – that is it, apparently, Daddy has not forgotten, good God, the wasps came and ate her, as simple as that, what more does a man know about the wasp, the hornet, a tale of two wasps that the Holy One, blessed be He, coupled and they both planted their venom in a man’s eye and the eye burst and he fell from a height and died, where is it, Daddy doesn’t recall, maybe in Tanhuma, with the torn mottled cover, never mind, what does it matter now, nothing matters, except Quick quick, faster, you beasts, get along there, faster, quick quick

And suddenly and in spasms, as if something inside him is trying to escape, or he cannot cope any more, as if some refusal is working inside him, some resistance from all his tiny being, and Mummy turns to him, and Daddy turns to him, the reins in his hands, his face wrinkled, his hair dusty, unshaven, his shirt sweaty, his arms big and gnarled, with straw on the backs of his big hands holding the reins, turning towards the child and all poured out and leaning, are they three people together here now, or each one alone not knowing what to do, with nothing to hold onto, and shudders go through the child, his blood is poisoned, his veins are nettle-rashed with poison, maybe right to the heart, and can he withstand it, how far has the poison got, and the terrible pain that the fainting absorbs for the time being, and prevents him shrieking, sobbing and flailing with his legs and arms, and writhing with this unbearable pain, what is pain, what makes pain pain, Daddy doesn’t know, Daddy who always knows more than others and always knows because he has always read something once and he never forgets anything he has read, but Daddy does not know what pain is or what happens in someone who has a pain, and this suddenly takes him away from the presence that is fixed on the child and he slinks away for a moment towards the extra knowledge of those who know how to know. What do they know about wasp stings, about the poison, about what it does to a person, let alone a little two-year-old child, so weak and frail, and what did he do to them to drive them mad, why did they suddenly swarm on him and inject venom into him, did he touch them with his little finger in their hole, or push a stick into the hole where their nest was and their babies, where they stood guard against any invader, what is this wasp anyway, what do we know about it, it is written in the Torah ‘And I shall send my hornet before me,’ and it says ‘none of your sting, none of your honey,’ in Midrash Rabbah, apparently, who knows any more about the wasp, this gold-colored bee, the big bee that eats bees, in the underground nest live the queen the workers and the soldiers, and these are the ones that were alarmed and came out in full force to repel the invader, what did he do to them, this invader, what was he capable of doing to them, he put in his hand by the hole, and suddenly Daddy recalls the tale of the maiden of Sodom who gave bread to a poor man and when the act became known they spread honey upon her and exposed her on the wall, and the wasps came and ate her – is it in Tractate Sanhedrin? – that is it, apparently, Daddy has not forgotten, good God, the wasps came and ate her, as simple as that, what more does a man know about the wasp, the hornet, a tale of two wasps that the Holy One, blessed be He, coupled and they both planted their venom in a man’s eye and the eye burst and he fell from a height and died, where is it, Daddy doesn’t recall, maybe in Tanhuma, with the torn mottled cover, never mind, what does it matter now, nothing matters, except Quick quick, faster, you beasts, get along there, faster, quick quick

And there’s more there, that it is permitted to kill a wasp even on the Sabbath, there are five things you can kill on the Sabbath, the fly in Egypt and the wasp in Nineveh, the mad dog anywhere, and the scorpion is there too, lucky it wasn’t a scorpion, lucky it wasn’t a snake, that it wasn’t a viper, a place swarming with desolation, and the scorpion in Adiabene, apparently, and the serpent in the Land of Israel, that may be killed anywhere, a place of snakes, always, and scorpions, a place in the world, a place lacking, a place lacking place, and a child that grows up in a place lacking place, and to raise a toddler in a place lacking place, Mummy will never forgive him, Mummy would be incapable of sitting a child down on a wasps’ nest, is it in Tractate Shabbat? Perhaps. It looks as though we can’t stay here. There was only one more strip left to finish and then we could go home, and he was sitting so quietly there, and all the time, how red he is, and so burning hot, let’s hope his windpipe isn’t blocked, he’s so tiny, and so many of them attacked him, why not me, they could sting me as much as they liked, and the wasp in Nineveh, and there are all kinds of other afflictions there, the grasshopper and the fly apparently, and the wasp and the mosquito, that one does not need to warn against but cries out against, if he is not mistaken, yes, behold a man before You, my God, crying out, to You, prepared to give all, would that I might take your place, my son, crying out, to You, and a child, so small, look, in this sunlight, in this heat, with this rushing, with this distance, and not an hour has passed, and everything now is just endless plain all totally empty, until the entrance to the village, with those children and dogs and all the confusion, such a remote faraway place, the male nurse comes once a week and what does he know, quinine, aspirin and dressings, and how to get a splinter out, or an ingrown toenail, what hurts a man when he has a pain, what is there in his body when he is attacked by the venom with which wasps stun their prey, and then they lay their eggs inside him so that when they hatch the larvae have rotten meat ready to hand, and the wasp in Nineveh, this bee, this wasp, the oriental one, there’s the German one too, if he remembers correctly from Berahm, and from Schmeil, with the illustrations, vespa orientalis, the golden one, and the German wasp, such a beautiful queen, with golden bands, and its narrow waist, that begins with a hole in the ground that it finds and it builds up with a material that resembles paper, with its saliva mixed with all sorts of leftovers, and when the nest is built it simply lays its eggs and the workers take care of it and gather food, while the males are only there for the moment of insemination, a nuptial flight, or is that only bees, a nuptial flight where only one of them possesses her and falls dead out of the sky. But not wasps, they tear the bees apart. With their golden bands. To feed their young. Faster, you beasts, faster, quick quick

And there’s more there, that it is permitted to kill a wasp even on the Sabbath, there are five things you can kill on the Sabbath, the fly in Egypt and the wasp in Nineveh, the mad dog anywhere, and the scorpion is there too, lucky it wasn’t a scorpion, lucky it wasn’t a snake, that it wasn’t a viper, a place swarming with desolation, and the scorpion in Adiabene, apparently, and the serpent in the Land of Israel, that may be killed anywhere, a place of snakes, always, and scorpions, a place in the world, a place lacking, a place lacking place, and a child that grows up in a place lacking place, and to raise a toddler in a place lacking place, Mummy will never forgive him, Mummy would be incapable of sitting a child down on a wasps’ nest, is it in Tractate Shabbat? Perhaps. It looks as though we can’t stay here. There was only one more strip left to finish and then we could go home, and he was sitting so quietly there, and all the time, how red he is, and so burning hot, let’s hope his windpipe isn’t blocked, he’s so tiny, and so many of them attacked him, why not me, they could sting me as much as they liked, and the wasp in Nineveh, and there are all kinds of other afflictions there, the grasshopper and the fly apparently, and the wasp and the mosquito, that one does not need to warn against but cries out against, if he is not mistaken, yes, behold a man before You, my God, crying out, to You, prepared to give all, would that I might take your place, my son, crying out, to You, and a child, so small, look, in this sunlight, in this heat, with this rushing, with this distance, and not an hour has passed, and everything now is just endless plain all totally empty, until the entrance to the village, with those children and dogs and all the confusion, such a remote faraway place, the male nurse comes once a week and what does he know, quinine, aspirin and dressings, and how to get a splinter out, or an ingrown toenail, what hurts a man when he has a pain, what is there in his body when he is attacked by the venom with which wasps stun their prey, and then they lay their eggs inside him so that when they hatch the larvae have rotten meat ready to hand, and the wasp in Nineveh, this bee, this wasp, the oriental one, there’s the German one too, if he remembers correctly from Berahm, and from Schmeil, with the illustrations, vespa orientalis, the golden one, and the German wasp, such a beautiful queen, with golden bands, and its narrow waist, that begins with a hole in the ground that it finds and it builds up with a material that resembles paper, with its saliva mixed with all sorts of leftovers, and when the nest is built it simply lays its eggs and the workers take care of it and gather food, while the males are only there for the moment of insemination, a nuptial flight, or is that only bees, a nuptial flight where only one of them possesses her and falls dead out of the sky. But not wasps, they tear the bees apart. With their golden bands. To feed their young. Faster, you beasts, faster, quick quick

Bareheaded, his short hair verging on blond and in fact already greying, and covered in dust, screwing up his eyes, moustache and mouth pressed tight, he pushes the mules that cannot and will not hurry faster or otherwise than their panting walk, their quivering skin flinching from the blows of the whip, unmoved by his cries, this is how they hurry and they know no other way, and this is how they will run all day and all evening and all night if that is their lot, hurrying neither more nor less, that is all that their mulish ability can manage, there is nothing to be done. What can be done my child, Mummy says to her chick who is huddled close to her, enwrapped in her, shaded from the sun, soundlessly sobbing, and Mummy, water? some water? but he doesn’t seem to be here, and she, rest a while like that, is that better for you? But he only writhes. And she, where does it hurt, mein Kind, where does it hurt, but he doesn’t seem to be there, and she, does my little boy hurt terribly? And she goes on, Mummy’s here, Mummy’s here, lay your head, and to Daddy, almost screaming, why aren’t we moving, why is it so slow, the child is burning the child is… are the three of  them together, or each consumed with their own care, and one of them is almost here almost not, Daddy whipping now and shouting now and the mules hurrying now, as they hurried before he shouted and before he whipped, and this bare plain all around, that only stirs up these dust clouds, above which the sun is moving now and seems to be starting to decline a little, and the horizon is full of sort of watery ripples, as though who knows what, or hints, or as though there it’s different, and only hurry along there, quick quick

them together, or each consumed with their own care, and one of them is almost here almost not, Daddy whipping now and shouting now and the mules hurrying now, as they hurried before he shouted and before he whipped, and this bare plain all around, that only stirs up these dust clouds, above which the sun is moving now and seems to be starting to decline a little, and the horizon is full of sort of watery ripples, as though who knows what, or hints, or as though there it’s different, and only hurry along there, quick quick

Like a nettle rash, and terrifyingly swollen, as though there’s no pulse in the pulse, only the sobbing of the pain that is beyond fainting, because he has not uttered a single cry beyond that first, terrible one that rent the world and the air and the sunlight, and at once his voice is silenced, from the pain and the swelling, and Daddy is already at his side, already he’s lifting him up, what is it, my boy, what is it, already waving them away with his hand and kicking them away with his foot, and flapping his hat, without being afraid of them, already running, where does it hurt, ruling out a snake or a scorpion and knowing already that it’s them, the wasps, the damned wasps, from the hole in the ground, on which he had put his baby to sit and amuse himself while he finished this strip, the last one, oh the strip of the field of this place that doesn’t exist yet, of this Co-operative Workers’ Association of the Herzl Forest Project, of Hapo‘el Hatza‘ir. Are they three people together now (or four, with the older boy, seven years old, who had been left behind), or three one of whom is guilty and needs to explain and apologise and even promise? So long as, so long as, God, so long as, I lift up my eyes, whence my help, out of the depths I cry to You, O Lord hear my voice, let Your ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication, and in a suddenly murderous voice, Get along there, faster, you beasts, faster, quick quick

|

Zeek’s translations of Hebrew literature are made possible with a grant from the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses, supported by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency. Please direct submissions and queries to arovner[at]zeek.net. This translation of S. Yizhar’s Preliminaries appears by special arrangement with translator Nicholas de Lange and publisher Matthew Miller of The Toby Press. Preliminaries will be published in May 2007 and includes a valuable introduction by scholar Dan Miron. For more information on this and other volumes of Hebrew literature in translation, please visit Toby Press. |

S. Yizhar is the pen name for Yizhar Smilansky, who was born in Rehovot in 1916 and died in August 2006. Yizhar’s parents were Russian immigrants and Zionist pioneers. He fought in the War of Independence, served as a Knesset member for parties led by David Ben Gurion for nearly two decades, and held professorships at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at Tel Aviv University. He published non-fiction, children’s books, short stories, novellas, and novels, including his untranslated masterpiece describing a battle during the War of Independence, Days of Ziklag [Yemei Ziklag (1958)]. Among his many awards, Yizhar received the Israel Prize, the Brenner Prize, the Bialik Prize, and the Emet Prize for Art, Science and Culture. Preliminaries [Miqdamot] was first published in Israel in 1992.

Nicholas de Lange has translated sixteen books from Hebrew, including Black Box by Amos Oz (winner of the H.H. Wingate Prize and the George Webber prize for Translation), The Same Sea by Amos Oz (joint winner of the TLS/Porjes Prize) and A Journey to the End of the Millennium by A. B. Yehoshua (winner of the Koret Jewish Book Award and joint winner of the TLS/Porjes Prize). He is Professor of Hebrew and Jewish Studies in the University of Cambridge.