February 07

February 07

Kishke, Culture, and Celebrity Chefs: A Conversation with the Food Maven

Leah Koenig

Five minutes into our meeting in the kitchen of his Park Slope, Brooklyn home, food writer Arthur Schwartz offered me a bowl of still warm, homemade applesauce. “I used my grandmother’s recipe,” he said, describing a rather short list of ingredients (“It’s just apples and a little sugar”) and the antique chinoise (a conical kitchen strainer) he had used to smooth out any identifiable chunks of apple. “I like adding a little ginger to my applesauce,” I said. “Yes, but then it wouldn’t be my grandmother’s,” he answered, not missing a beat.

Five minutes into our meeting in the kitchen of his Park Slope, Brooklyn home, food writer Arthur Schwartz offered me a bowl of still warm, homemade applesauce. “I used my grandmother’s recipe,” he said, describing a rather short list of ingredients (“It’s just apples and a little sugar”) and the antique chinoise (a conical kitchen strainer) he had used to smooth out any identifiable chunks of apple. “I like adding a little ginger to my applesauce,” I said. “Yes, but then it wouldn’t be my grandmother’s,” he answered, not missing a beat.

During the course of my guided Jewish culinary tour of Brooklyn, Schwartz shared his views on everything from contemporary food culture (including aversions towards celebrity chefs like Mario Batali and Bobby Flay as well as expensive martinis – opinions I definitely share) to the state of Jewish cuisine in New York City (mostly dismal) to the trouble with contemporary food writing (according to Schwartz, many young food writers are not – excuse the pun – worth their salt). As a young, aspiring food writer myself, many of Schwartz’s comments sounded “old school” – not in the sense of being negative or out-of-date, but more in a “I can’t believe this man renders his own schmaltz” (true story) kind of way.

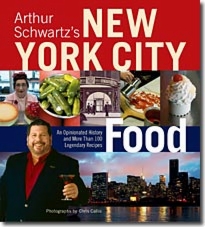

Schwartz – known in New York City as “The Food Maven” – has been writing about food for thirty-eight years, having served as the restaurant critic and executive food editor at the New York Daily News and hosted the popular show Food Talk on WOR talk radio. His encyclopedia-length cookbooks including The Big Book of Southern Italian Food and Wine and Arthur Schwartz's New York City Food: An Opinionated History and More Than 100 Legendary Recipes prompted the New York Times Magazine to call Schwartz "a walking Google of food and restaurant knowledge.” In recent years, he and his partner in both life and business, Bob Harned, opened a travel and cooking school, flying participants to southern Italy for hands-on culinary instruction, lavish meals, and tours of nearby ancient temples.

Schwartz and Harned escorted me from Park Slope to Midwood for a stop at a kosher butcher tucked inside of a large supermarket. Bob and I chitchatted near the cash registers while Schwartz, unaffected by the scent of raw meat permeating the back quarter of the store, negotiated his preferred cut of beef. Next, we stopped at a parve kosher bakery, its majestically decorated cakes glistening alongside black and white cookies and crispy sufganiyot (jelly donuts) bulging with synthetic raspberry filling. The highlight of the afternoon was lunch at Mabat, an Israeli grill just off kosher restaurant row on Kings Highway: We ordered an abundant spread of colorful salatim (Israeli salads and spreads), hummus and falafel, lamb chops, and vegetarian snieya, caramelized mushrooms and onions resting on a second plate of falafel.

As we sat facing each other at Mabat, four decades of Schwartz's thinking about food mixed in with our meal. Though I was not willing to concede his point that young food writers should withhold their opinions, I knew that one doesn’t get the title “The Food Maven” for nothing. There was a lot to learn.

Leah Koenig: You’ve been writing and talking about food in New York City for the last thirty-eight years – long before 'food writing' became a named profession. When you first started, what sort of response did you get? Did anybody take you seriously?

Arthur Schwartz: That’s an interesting question. My first job was as the assistant food editor at Newsday [in the late 1960s]. Nobody really took the food pages seriously because they were mostly edited by women who knew nothing about food but were given the job because they were women. My first boss at Newsday was a reporter and they needed to do some food [articles] in the paper, so they said, 'OK, you’re a woman – do the food pages.' She was a terrible cook who knew nothing about food. I think I got my job because she finally needed to hire an assistant. Some people who were intimidating to her because they did know something [about] food applied for the job. I think I got it because I was just a kid.

LK: And what did 'food pages' mean at that point – were they all recipes and reviews?

LK: And what did 'food pages' mean at that point – were they all recipes and reviews?

AS: Recipes and feature stories that were mainly about people. At Newsday my job was to go out and interview local women who were good cooks. In those days on Long Island there were a lot of ethnic cooks – a generation of women who spent their lives keeping house and keeping their families.

LK: Who were some of the women that you encountered when you first started writing for Newsday?

AS: Well, Long Island was mainly Jewish and Italian with sprinklings of other things in there. Within the Jewish umbrella they were Polish, German, Hungarian...which all had different foods. I would go to their houses and cook with them. These were people who didn’t necessarily know how to write a recipe. So the only way to get a recipe from them is to cook with them. And I had done that with my grandmother and grandfather. Every time they went to add something to the pot, you’d stop and put it in a measuring spoon.

LK: Did you have a sense in those early years that you were creating a new genre?

AS: No, not at all – we were just doing it. [Early] food writing [was written] to support supermarket advertising. The big change came in the late 1970s, when national food advertisers started putting ads in the daily newspapers. Those new ads created spaces that needed to be supported with editorial. So that’s when all the food sections started appearing across America.

LK: What do you think about the direction food writing is taking today?

AS: Now every kid wants to be either screenwriter a food writer! You can actually study food writing in college these days. But you know, there’s only so much work.

LK: So how does that change the industry?

AS: My third replacement at WOR said something so true this morning. He said, 'There’s a lot of food writing out there, but not very well informed.' They don’t know anything – and it’s all on the Internet, so there’s often less of a screen. Even large publications like Time Out have people [who don’t know anything] about food offering opinions that make or break people’s business.

LK: If there are so many people who want to be food writers, can’t the publications be more selective about who they publish?

AS: Well they don’t want to pay much. I used to teach food writing. And everybody [wanted] to write about their grandmother’s cooking. But you need to have reporting skills! You need to have information – not just write about opinions and nostalgia. I didn’t voice my opinions until I was writing for ten years. I didn’t think I had any right to. How much taste experience can you have when you’re 25?…How old are you?

LK: I don’t want to tell you.

AS: You’re 23.

LK: Almost 25. Don’t fault me for it!

[We were interrupted by Elan Kornblum who publishes Great Kosher Restaurants Magazine. He and Schwartz chatted briefly about doing a kosher food tour together. I asked Harned if this sort of recognition happened all the time. “Yes,” he answered. Almost as if on cue, our waitress arrived with a plate of grilled onions we didn’t order. “To what do we deserve this?” Schwartz asked. “They come with falafel,” she demurred. I noticed that none of the other patrons who had ordered falafel had a plate of the fragrant, charred onions on their tables. I told myself that I could get used to this.]

LK: I read in your bio that your grandfather was a professional chef who ended up working as a waiter in a Jewish dairy restaurant. Which restaurant did he work for?

AS: It was called The Famous on Eastern Parkway and Utica Avenue. He also worked at a Romanian steakhouse, a famous place called The Little Oriental, which was on Pitkin Avenue. In its heyday, which would be the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, [Pitkin Avenue] was a fancy, mainly Jewish shopping street. The Borough president at the time, Abe Star, had a haberdashery on that street. And the Little Oriental was the place everybody used to go – if they had money. When that closed my grandfather went to work at the Famous, which had the same clientele. There’s now a McDonalds there.

LK: What was it like to visit him in the restaurant growing up? Did your family eat there?

AS: He hated it, so we didn’t eat there very often. We lived in Marine Park, so we ate at a few Chinese restaurants, a few delis and Italian restaurants. And we’d go to Manhattan. The real Chinese food didn’t get [to New York City] until the mid-1960s when the Chinese Exclusion Act was rescinded. As soon as it was rescinded, we got an influx of good Chinese chefs who did all the regional things. When I got married in 1969, the big thing was to go eat cold sesame noodles and other spicy dishes that didn’t exist before that.

My parents’ first date was at a Chinese restaurant. There’s a joke – I’m making up numbers, but if the Jews are in year 5740, and it’s 5700 on the Chinese calendar, what did Jews eat for 40 years? You must have heard that one.

LK: Yeah, though only recently. Speaking of Asian food though, I notice now that there’s sushi everywhere in kosher restaurants. Even kosher pizza places have sushi bars attached to them!

AS: Absolutely. I think the first sentence of my new book is, 'If a kosher Martian landed in New York, he would think sushi is the most Jewish food on Earth.'

LK: Do you think that’s an extension of the Jew’s fascination with Chinese food, or something different?

AS: No – it’s Jews being part of the culture at large. Interestingly though, the new meal at a Jewish steakhouse is sushi as an appetizer and then a steak. Sushi has taken the place of gefilte fish as a first course.

LK: It seems like the era of egg creams and the 2nd Avenue deli is coming to an end. What are your thoughts on the current state of Jewish eating in New York City?

AS: I was just calling around yesterday and there’s a diner on Linden Boulevard on the border of Queens. It’s owned by Caribbean people – and they serve egg creams! But overall it hardly exists, which is very sad to me. Just about a year ago [Bob and I] went to Sammy’s and it was disgusting. Sammy’s is one of the last of the Yiddish Romanian steakhouses. It’s on Chrystie Street on the Lower East Side. The food was disgusting – and that’s really the last of them.

But it dawned on me, Katz’s pastrami [also on the Lower East Side] is the last great pastrami. There’s pastrami around, but there’s no place other than Katz’s that’s worth eating.

You know, I have a lot of recipes in my new cookbook that I think are going to be a revelation to people in your generation. Like the meat I’m going to make tomorrow for Chanukah – sweet and sour flanken. Nobody makes that anymore, except a few Chassidim maybe. And kishke! Nobody makes kishke anymore. Traditionally kishke is packed in an intestine, but it’s just a starch sausage. I made up my own recipe – I make it in tinfoil. It’s basically nothing but matzoh meal with carrot, onion, and celery. If you want it to have good flavor, you should put some schmaltz in there, but you could make it with olive oil and it’s still very good.

LK: What is your book called?

AS: It’s going to be called, Arthur Schwartz’s New York Jewish Food: Strictly Kosher Mostly Yiddish Cooking Revisited. I’m hoping it will be out next November to coincide with Jewish Book Month.

LK: I like the word 'revisited' in there. It leaves room for a few twists.

AS: Cucina Revisitada is a phrase used in [contemporary] Italian cooking. It means traditional food that’s somehow been tweaked for modern palates.

LK: It’s like the Modern Orthodoxy of food.

AS: Correct. I’m not going to have sushi recipes in there, but I do have this kishke, which has a much larger proportion of vegetables to keep it moist instead of fat. The recipe still tastes like the old time recipe, but it’s more acceptable to the modern palate.

You know, after World War II, really from the 1930s through 1950s, mainstream New York menus had Jewish food on them. You could go to a mainstream restaurant where the appetizers were shrimp cocktail and gefilte fish. Or the soups would be mushroom barley and lobster bisque. Or underneath the grilled ham with pineapple was brisket. Every New Yorker ate these dishes. There were the assimilated Jews who ate shrimp cocktail and the gentiles who liked gefilte fish. And that doesn’t exist anymore. The ethnic blending is over in New York. Now it’s all 'chef food.' To me, food is not just something just to eat, it’s also a reflection of our culture. Of course the chef food is also a reflection of our culture. But it doesn’t speak well of our current culture [laughs], when I see Mario Batali on television boiling pasta in red wine and topping it with cranberries, it just doesn’t speak well. I enjoy food that has context and culture.

LK: Food that tells a story.

AS: Right. [The current reign of celebrity chefs] doesn’t interest me. Just to put it mildly. I think as you get older you start editing out the stuff that doesn’t interest you. Fortunately in my career I don’t have to be interested in that anymore. For a long time I did. Also, I can’t afford it!

Just the other night we went to a friend’s party and there was a chef there who told me where she was working and I said, 'Oh I guess it’s nice but I can’t afford it.' She said, 'We just reduced the price – our pre-theatre dinner is $42 for three courses.' I said, 'After tax and tip that’s $55 with only a glass of water! If I want a glass of wine that’s now $80.' A cocktail in Manhattan is $14 or $15! I can get a cocktail on 5th Avenue [in Brooklyn] that’s just as good for $7. And I can have it at home - kena hora I know to mix a cocktail [laughs]. Somebody said to me the other day, 'What do you think of this new word, mixology?' It’s not new! It’s one hundred years old, if not more! Young people think they invented it, but you know, nothing is new. Maybe cooking spaghetti in red wine and putting cranberries on it is new, but almost nothing is new.

Leah Koenig is an Assistant Editor at Zeek. Her food writing can be found on the new blog The Jew and the Carrot