December 06

December 06

The Unadulterated Projectionist

by David Stromberg

p. 2 of 2

Looking at the green-brown muck all around, with its cows and its fences and its barns and its tree here and there, Boris had to admit he could certainly never give up his involvement in the world, as marginal as it was, for a life this irrelevant and removed. He was a social being despite his ever protest against it. So how could he expect Hitler, who saw himself as having considerably more influence and relevance to society than Boris, to give it all up for a plot of cow food? Boris, too, was passing through this pasture on the way to other lands, perhaps not looking to conquer a people and a state, but nonetheless with the intention of acquiring and owning a tiny portion of its cultural history. Well, but he was paying good money for his few film reels, and gaining possession of them by consent of their owner. Whereas Hitler, well, he wanted it all for free, and against everyone's wishes. Stubborn brute. Cheap boor.

The blowing of the train's horn called back all straying passengers - the sound was faint, proving the distance between Boris and the train to be farther than was apparent - and if he didn't hustle back he might really be altogether abandoned at this pasture, a prospect that for him, perhaps like for Hitler, really was not so enticing.

Book IV: The Informed Peasant

Yana's mother lived in Neve Ya'akov, a neighborhood so small and segregated from the rest of Jerusalem that it was mostly considered an outlying village, and, in fact, was known - if someone knew it - only for being remote and difficult to reach; and, what was more, completely not worth the distance and difficulty necessary to reach it. Its unofficial title was the Neighborhood of Gold Teeth, named after all the Bukharian and Russian immigrants who moved to Israel with little more than the yellow ore crowns covering the rotten roots of their oral orifice. Yana lived in this neighborhood not so much as a resident, nor a guest, but more as an entity perpetually passing through. The neighborhood infrequently acknowledged her presence, and she even less so asked anything of it. They tolerated each other the way the street-signs tolerated the cars that passed them.

Yana sat under the orange light of a streetlight on a short white-stone fence at the street-end of Neve Ya'akov's "center": an open-topped pavilion lined with several small convenience stores open till late in the evening, where one could buy cigarettes, beer, water, gum, pickles, a pastry, salted fish, cheese, milk, a bottle of wine; a shop which sold a mix of clothes, discontinued shoes, plastic goods from toys to kitchenware, all products with no clear origin in style or intention; a pharmacy which was open only the first half of each day; a small second-floor synagogue; a supermarket which closed early in the evening; a post-office which closed in the late afternoon; a new pizza parlor that stayed open late; and a restaurant and ceremony hall under construction, having taken over the space where the only local bank branch had been, and where now there was only a cash-machine. It was eleven-thirty at night, by now everything in the pavilion was closed, and the only preoccupying product she could get while she waited for Sherman to arrive was a pack of cigarettes, to be purchased from a vending machine next to the neighborhood's gas station on the other side of Yana's mother's apartment building.

The gas station was connected to the parking lot flanking the broad side of Yana's mother's apartment building, which looked out in the direction of Jordan, whereas the pavilion was adjacent to the side facing the center of Jerusalem. Leaving behind the pavilion's mishmash of teenage and elderly late-night loafers, Yana walked, unnoticed, anonymous, in the Jordanian direction, through one entrance of the apartment building and out the other, weaving past parked cars, passing by, but not getting too near to, the neighborhood police station, which stood next to the gas station and operated all day and night, but which was not a place for entertainment or diversion, at least not for anyone unwilling to break a law or pose a threat. There were usually two or three policewomen and policemen loitering around the station entrance in their loose dark blue trousers and looser light blue shirts, with braided black bands hanging over their shoulders to designate their rank and a gun or two hanging from their belt or shoulder to designate the extent of their force - leaning back on the metal barricades that set the police station apart from the parking lot and the gas station, they didn't seem at first to be in the tensest of states, but beneath their nonchalance was a detectable potential for severe formality, for professional harshness.

Yana turned right into the gas station, its whiter light was given a blue tint in contrast with the orange of the street lamps; she dropped all the coins she had into the slot, and, after selecting a pack of Time cigarettes, she passed back by the pumps with their locked-up nozzles and, having as usual forgotten to bring matches, she finally approached the chatting police officers and asked for a light. Though those few words she uttered in her slightly Russian-tinged Hebrew - "Do you have a light?" - were instinctively and correctly said, they hung in the vacant night air with blunt distinction from the streaming native Hebrew she had interrupted. There was something in her voice - not the formulation of her words, not her "accent," but her actual voice, the way she projected sound from her throat - which acknowledged with every word, "Yes, I'm not from here; if you want, you can pretend I'm not here at all." Heeding that unsaid yet vocalized admission, a policewomen no older than Yana, who had been mid-sentence when Yana made her request, uninterestedly pulled out a lighter, brought the flame up to the cigarette hanging out of Yana's mouth, and pulled it away, continuing the monologue about her brother's idiot wife which the slightly older policewoman listened to with weary, encumbered absorption.

Rather than returning the way she'd come, through the apartment building, Yana walked back to the center along the main road, which made a loop down, up, and around the outlying hill. Apartment buildings, extending north and east from the pavilion, made up the totality of the neighborhood. A mix of new immigrants - Bukharians and Russians, along with Ethiopians, Georgians, and Moroccans - lived around the upper portion of the hill, close to the pavilion and just under a large army base that crowned the hilltop. On the slightly lower flank of the hill, above the white-rocked foothill that descended into an uninhabited valley and ascended toward Arab villages, was a dense conclave of Hassidim, who, besides having a few small congregations and study rooms established in rented, second-floor office spaces above the pavilion, worshiped in synagogues which could be found by walking in any direction.

Now, close to midnight, as Yana sat watching the bus stop across from the pavilion, looking for Sherman to get off one of the busses, she could see Hassidim sitting or standing throughout the crowded busses, some holding religious texts close in front of their face, some chatting, all waiting for the next one or two stops further down the hill, while smartly dressed teenagers and bag-toting elderly exited the bus and dispersed, some to the monolithic twenty-five-story apartment blocs behind them, some to the smaller three- and five-story apartment buildings along the neighborhood's edge, and some to the pavilion itself, to sit and pass time.

A teenage boy with blond highlights separated from his pack and walked over to Yana, who was sitting at a remove from the sidewalk on a large white stone under a low tree; he asked her for a cigarette, and she pulled one out of the box and gave it to him. He asked her for a light, and remembering that she didn't have one, she looked at her own cigarette and saw that if she intended to have another smoke she would be needing another one soon, too. She lit his cigarette with what was left of hers, and immediately lit another cigarette for herself, hoping that Sherman would arrive soon so that she wouldn't have to chain smoke the whole pack.

Book V: The Habit of Reinvention

Schneier Scheinhorn wanted to become a white-stone Jerusalem building. How could he become such a thing? Could he simply splatter himself all over its facade of rocks, leave there the residue of his blood, innards, and splintered bones? Could he jump to his death onto a building?

And anyway, it wasn't death he aspired to, it was for the sake of life that he wanted to jump - to jump to his life - jump in order to save himself from the anguish he knew was not a part of him, and yet was still there: the anguish that projected itself onto everything it possibly could, everything there was.

Splattering himself on a wall could help, after all, in another important way: it could help relieve some of the accumulated vodka he had started drinking unremittingly two years before, not long after his arrival in Israel - a reservoir of alcohol that had dispersed and settled throughout every nook of his body, the gazillions of molecules of hydroxyl compound that might evaporate at least in part once his lungs and liver and kidneys had a chance to air out, once his arteries had a chance to swing freely in the city's cool evening breeze.

Having spent every single day of his sixty-three years in the Belarusian town of Berezino, Scheinhorn left immediately upon his release from the Berezino Province Jail Detainment Annex, into which he had been emplaced for nine months for abetting lewd conduct. His sudden emancipation was as mysterious as his original confinement had been unwarranted. To his credit, he attempted during those nine months to produce a not-too-long text, a journal centered around the events that had landed him there; but, upon reflection, he found that the work over-philosophized banal issues which he had at best an indirect relation to, and over which he could grant himself at most a dubious, unreliable authority.

Morally loath to retreat to his row-house, unwilling any longer to bear Berezino's degenerate core, Scheinhorn had looked to the Modern State of Israel for asylum, which, as a matter of course, it gave to him the same way it had given it to near one million other ex-Soviet Jews; a few provisions were promised him - the opportunity to buy household appliances without the usually heavy taxes, a meager monthly stipend, and free healthcare - but as he had neither a household nor the capital to buy appliances (which, in theory, he would then resell for a slight profit), all he was left with was $300 per month, and a hospital bed or a visit to a doctor, in case, God forbid, he ever needed either one.

Scheinhorn had been assigned to a small absorption center for older olim not far from the Russian Compound in Jerusalem's center, and when his absorption program ended one cool autumn day he was released, hatted and sweatered in his dark gray slacks and with a small doctor's bag, into the city, where he was supposed to establish for himself a mollifying routine. But using some self-acquired elementary accounting from his brief period as land-owner, Scheinhorn gathered that even renting the smallest furthest-away flat in Jerusalem would not leave him with enough money to cover what was necessary for basic sustenance; not to mention that discarding Jerusalem, into which he had spent such effort being absorbed, in exchange for some cheaper, smaller, or more welcoming community would have demonstrated yet another moral compromise: a rejection of the anonymity and inconsequence he had delivered himself into, a return to the insular, parochial concerns of cohabitants that would likely agree prejudicially on the very issues that required dialogue, debate, and disagreement.

Unable to find his way through this dilemma using logic, reason, or accounting, Scheinhorn bought himself a small bottle of vodka and, taking it to Independence Park, sat down on a bench set into an alcove under the shade of a willow, mulling over his whole predicament to the hankering beatings of a beginner's darbouka class coming from a community center on the other side of the fence-wall behind him. In thinking about himself and the city, Scheinhorn found respite in Jerusalem's contradictory qualities: the mayhem and unconcern of its markets and stands, the touristic and pious preoccupation of its center, the manifest and distancing austerity of its religious devotees, the enduring pining for peace and the unyielding imminent danger, the adamant phenomenon of its Jewish governmental body and the resentful persistence of its Palestinian presence. All these things together in one complicated, yet finite, yet mysterious, yet welcoming, yet severe, yet generous, yet limiting, yet inexhaustible place - which he couldn't afford.

His attention having been fixed on these thoughts as they took shape, he had finished the entire bottle of vodka without really noticing. Then, overcome by a physical urge to disengage which simultaneously put his mental capacities out of commission, he laid down on the bench and, also without really noticing, fell asleep - a slumber during which his internal constitution was steadily both annihilated and reconstituted, mutated rather than ruined, resulting in a Scheinhorn that was still Scheinhorn but somehow no longer. And it wasn't so much that he liked the new Scheinhorn than that he liked taking a break from the old one. So that not thinking but escape had solved his dilemma: from that afternoon on, there would be vodka and a bench.

And yet, despite having slept every afternoon for more than a year and a half either in Independence Park, at or around Zion Square, or in Saker Gardens, neighboring the Israeli Defense Force's base in the city center and the Knesset, not far from the Israel Museum, Scheinhorn would have felt like a liar saying he had become Israeli. He could manage about five words in his sixth language - piled on top of Russian, Belarusian, French, and some Spanish and Italian - Hebrew, the language in which he intended to live out his advancing years, the language in which he was supposed to read the Torah, the language of his people, the reclaimed language, the re-organized language, the language of his Israel, the language of his missing Israeli ID card. Curiously enough, there was no Russian accent traceable in his Hebrew - perfect intonation with all nine words he could say - but what? Did that make him Israeli?

Of course.

Or. Not.

Could he become Israeli? Could he, at sixty-five, take the responsibility of Israel onto himself, all by himself?

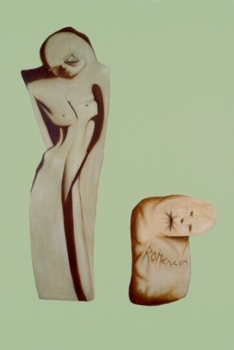

David Stromberg is Zeek's new Book Reviews editor. He was born in Ashdod, Israel, and, at the age of nine, moved to downtown Los Angeles. He holds a BS in Mathematics from UCLA, an MFA in Writing from CalArts, and is the author of three collections of single panel cartoons, Saddies (featured four years ago in Zeek), Confusies, and Desperaddies. He lives in New York City and is at work on his first novel, from which these passages are excerpted.