July 06

July 06

Israeli-American

by Yoav Fisher

p. 2 of 2

That morning I'd been on the phone with my good friend Edan. He had just finished his BA in electrical engineering from SF State and tonight was his graduation party. During the day, he was in school, and at night, he taught Hebrew class at Temple Emanuel to the pubescent kids of the upper middle class Jewish population of the city. He was part of my Israeli friends, who did not mix with my American friends. My attempts to combine the two groups had been disappointing. Beyond the typical niceties and innocent flirtations, it was clear that no substantive associations had emerged across the groups. Edan, like my parents, related to the non-Israeli Jewish community of San Francisco only in situations where he had to, like in lectures or study groups. Every other moment was strictly Israeli. Most other teachers at Emanuel were similar: all recent immigrants to the States, all pursuing their own version of a “finding yourself” quarter-life crisis. They went out together, played pickup soccer together, and went thrift-store shopping on the Haight together. In this sense, these Y-generation Israeli immigrants shared the same characteristics as my parents' generation of Israeli immigrants, namely a perceptible separation from the larger Jewish community, as well as a marked affiliation with all things Israeli.

“I understand why your mother seems to be opposed to you moving back,” my uncle took his last sip of cappuccino and reached in to his jacket pocket for his cigarettes, “You are basically subverting all the reasons she left Israel to begin with.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Your parents left for very simple reasons,” my uncle lit a cigarette, “First, whatever future they wanted for themselves simply didn’t exist in Israel, and second so their children would have the opportunity to live easier and more normal lives. Now you are planning to do the exact opposite. You are moving away from the land of opportunity and putting yourself back in the mess they tried to avoid.”

“But it has nothing to do with my parents,” I protested, “It’s my choice to go back”

“And that is what is the most frustrating to your mother. You are an adult and you make your own decisions. It would be much easier for her if you were ten years old and she could just tell you no, you are staying here with mommy and daddy.”

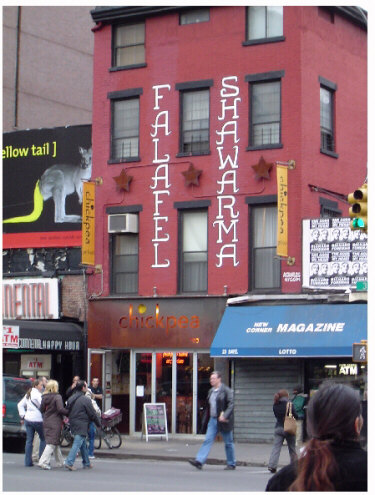

I realized then that Edan and the rest of my Israeli friends immigrated for the same reasons as my parents and their friends. Israel still suffers from the same insecurity, instability, and political turmoil as it did thirty years ago when my parents got married and first started thinking of leaving. And the reality was that my uncle was largely right: I and most of my friends were children of the baby boomers, and probably did have a diluted understanding of the day-to-day complications of life in Israel. To us, Israel meant doting grandparents, weddings for second cousins, days on the beach, and falafel. To recent immigrants, regardless of the generation, Israel signified familiarity, but also the difficult tradeoff of leaving behind all that was known in the hopes of a future of calm and normalcy.

Still, like most first-generation immigrant groups, Edan and my Israeli friends continued to cling to the familiar, surrounding themselves with other Israelis who share the same mentality, history, and upbringing. Meanwhile the second generation, people like me, have benefited from the easier lifestyle afforded to well-off Americans, and are rooted and connected to that lifestyle. There are thus distinct differences between second-generation Israeli Americans on the one hand, and on the other, first-generation immigrants and family or friends who remain in Israel. The differences are in the smaller nuances of life, like the use of language, social norms, or fashion. But these minor idiosyncrasies do create a binary nature in Israelis living in America, where new immigrants are distinctly Israeli, and their children are distinctly Americanized.

“Listen,” my uncle took the last drag of his cigarette, “I understand that you feel like you have an Israeli identity. Everybody wants an identity.”

“Not exactly”, I interjected, “I feel like an Israeli when I’m here, and I feel like an American when I’m there.”

“But that is how it is always going to be. You grew up in America, but your Israeli passport is with you for life. It’s like herpes; you can never get rid of it. Just some people have worse symptoms than others, and some have worse flare ups than others”.

“And now I’m going back, which is only going to make it more confusing,” I was thinking out loud.

“You have to think about it positively. Clearly you have to get this out of your system, and hopefully you will get a better understanding of where you belong. And even if you don’t you will probably meet some Israeli girl who used to be a tank commander and she will decide for you.”

“My mother would be thrilled”, I laughed, “I just have to figure out where to find her”

“That’s a whole other conversation”, my uncle winked.

Yoav Fisher is cofounder and frequent contributor to Newzionist.com, an online journal about the future of Israel, Zionism, and Jewry in general. He currently lives and works in San Francisco and is returning to Israel this fall to pursue graduate studies in Economic Development of the Middle East.