June 06

June 06

Voting Kinky: The Politics of Ridicule

Sarah Lefton

"An Asshole from El Paso": Kinky Friedman

Kinky Friedman is out to save the world, in his words, “one governor at a time.” He's out on this year's Texas campaign trail, running for Governor. Now, if you don't live in Texas, or aren't a country music fan, or hate mystery novels, or don't keep tabs on Jewish cowboys, you might be forgiven for not knowing who Kinky is. Perhaps a good introduction lies in his song:

I’m proud to be an asshole from El Paso

A place where sweet young virgins are deflowered.

You walk down the street knee-deep in tacos

Ta-ta-ta-tacos

And the wetbacks still get twenty cents an hour.

Kinky's been playing obnoxious country music ("Get your biscuits in the oven and your buns in the bed") since he formed his band, The Texas Jewboys, in the early 70s. He ante-dated Borat's Jew-pretending-to-be-an-antisemite shtick by over a decade in songs like "They Sure Don't Make Jews Like Jesus Anymore." He's known as a detective novelist (Bill Clinton and George W. Bush are both big fans) and an animal rights activist. And endearingly, he makes his home at Echo Hill, a Jewish summer camp his parents started in western Texas.

Granted, running as a Jew in an overwhelmingly Christian state has its rocky moments, and Kinky hopes no one remembers what he said about the Baptists ("They don't hold 'em under long enough"). He's got a platform: the "dewussification" of Texas, giving gay people the rights to get married and to be “as miserable as the rest of us," doing away with the death penalty, giving rights to illegal immigrants and getting the hell out of the way so that smart people can do their jobs. Defiant and at first blush, unserious, running with the campaign slogan, "Why the Hell Not?” his campaign reminds one of Jesse Ventura's surprisingly successful 1998 run in Minnesota.

Running for office in a modern, mediated society is a perhaps the most exhausting, expensive, demoralizing battle a person could possibly wage. Yet year after year, in democracies worldwide, marginalized, creative, activist dreamers arise and declare their candidacies against the entrenched power structure. In recent American history, we have enjoyed the spectacle of such moderately serious candidates as Kinky Friedman and Jesse Ventura, as well as Jello Biafra's amusing run for Mayor of San Francisco and Wavy Gravy's "Nobody for President" campaign. We’ve also seen the sharp satire of Michael Moore's 2000 FICUS for Congress campaign ("Because a Potted Plant can do No Harm").

"Electoral Guerilla Theatre": L.M. Bogad

L.M. Bogad, Assistant Professor of Theatre and Dance at UC Davis, has written a history of such campaigns in his new book,

Electoral Guerilla Theatre: Radical ridicule and social movements. Coining the term in title, the text begins with an academic survey of political thinkers who hold up the stage as an important venue for radical social change. This includes Soviet exile Mikhail Bakhtin, who claimed that the "carnivalesque" brings a kind of liberation to the lower class, insofar as "it is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates." It also includes the German director Bertolt Brecht, who took the politics of stage theatrics one step further and dreamt of a theatre that actively alienated audiences, exposing class conflict and oppression. This notion of Verfremdungseffekt was likened to a hammer which could reshape society. Audiences were not meant to be swept away emotionally by what they saw on stage, but rather to be shocked into recognizing the truth.

Bogad has written an academic book that is clearly informed by both a passion for activism and an awareness of the fragility of social movements. Working with organizations like Billionaires for Bush, who stage ironic shows of faux upper-crust support for President Bush, and Reclaim the Streets, which is devoted to non-violent actions like illegal dance parties in the middle of public streets, his deep knowledge of the history of political theater has got to be an asset for those organizations. Overall, reading Electoral Guerilla Theatre is like taking a good course from a slightly verbose lecturer. A fascinating chunk of political history is uncovered and laced together in ways that seem useful to the reader as activist. The book is a good read, if not a toolbox, for those involved in street performance as political action, and anyone planning a campaign to promote marginalized issues or populations. It is also an interesting commentary on the theater, particularly for readers who typically don't like their politics mixed with their drama habit. Regardless of whether or not you've studied theater academically, Bogad’s case studies illustrate how actions onstage, with or without the curtain, can create public awareness of inequity, and lead to concrete change. Of course sometimes, the acting falls flat, the reviews are terrible, and the audience rolls its eyes with disdain.

Despite the theatrical polemics and academic musing, however, Bogad asks readers vital questions. What happens when those on the fringes of society – bright, talented and organized – are still not taken seriously by the mainstream? Can they possibly hope to join the civic conversation about issues like housing, racism, public transportation? Will the nightly news report the views of anarchists, queers and communists? Can they join their less-articulate, better-funded and better-dressed competition on the floor of national political conventions? Experience tells us no, and that those on the far left in particular – who favor consensus-driven decision-making and prioritize local community over international politics – are doomed to being shut out of high level media conversations about society.

Despite ridicule by the mainstream, sometimes, these fringe forces rise up and use that very ridicule to get their message across. Taking a stand in intentionally ludicrous ways, they rally behind drag queens, street performers and the occasional ficus. Bogad, in his book, takes us into three fascinating histories of theatrical activists who made their mark on society through very different candidacies: in Chicago, in Sydney, and in Amsterdam.

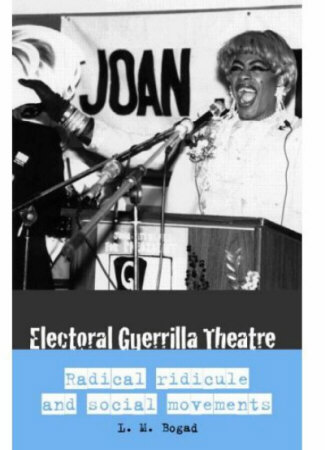

"Rituals of legitimization for extant corrupt political structures": Joan JettBlakk

Joan JettBlakk, the creation and "soul sister" of Chicagoan Terence Smith, is a queer black drag queen who dons a masculine look in her dresses and fishnets. No fake breasts here; she's interested in gender confusion, not illusion.

Queer Nation/Chicago, an activist group that JettBlakk co-founded, asked Joan to run for Chicago’s 1991 mayoral race, for just the final three weeks of the campaign, in order to attract as much visibility as possible to queer life in Chicago. An absurd as idea as it was to run a drag queen against the Chicago Daley dynasty, Queer  Nation bristled at the easygoing re-election farce and became determined to disrupt it however they could. JettBlakk rolled with the absurdity and embraced her freedom as a preposterous candidate to make speeches about universal healthcare, lowering taxes, the abolishment of parking tickets and the advent of gay marriage. In her own words, "Fuck Dick Daley, with my dick, daily."

Nation bristled at the easygoing re-election farce and became determined to disrupt it however they could. JettBlakk rolled with the absurdity and embraced her freedom as a preposterous candidate to make speeches about universal healthcare, lowering taxes, the abolishment of parking tickets and the advent of gay marriage. In her own words, "Fuck Dick Daley, with my dick, daily."

Was this queen really running for mayor? Of course not -- but the visibility that her campaign brought to queer people and ideas in the local media was irresistible, and so Queer Nation decided to extend the farce towards the race for the U.S. Presidency. The purpose was not just to force mainstream journalists to address issues of queer identity, but to radically force a clash of ideas with gay community leaders less inclined to rock the boat of social norms.

Most minority groups struggle between separatist and assimilationist forces. Presumably the latter camp has the larger constituency, with most folks just fighting for civil rights and decent lifestyle. Yet those on the edges often make the most noise. Queer Nation made a hell of a lot of noise, rejecting the notion that LGBT people were just like anyone else. Moderates can argue, for instance, that gay marriage is an idea whose time has come, but Queer Nation would more likely decry the institution at large, arguing that it is corrupt, heterosexist and inappropriate in a modern diverse society. Employing camp to decry such institutions and illuminate their social pain, JettBlakk used the pun "camp-pain" to describe her “campaign.”

JettBlakk and Queer Nation were well aware of their place in the history of political theater and referred occasionally to related campaign.

"A lot of people say that…I became an art piece instead of a candidate, but one of the things I had in my mind the whole time I was doing it was that this was always a performance piece. It was always a prank…Jello Biafra ran for Mayor and Abbie Hoffman had some wonderful things to say about ways to fuck with the government and I really believe that running for President was a great prank to pull on everyone." (JettBlakk, 1992.)

Drag candidacy was not about winning. It was about using the electoral process to draw attention to its own absurdity and point out the unfairness of there being only as anointed few on the floor of the Democratic National Convention? After all, should wearing a wig and Cleopatra-esque makeup mean you can't get into Madison Square Garden? Why should those disillusioned with the two major parties have their votes wasted? As guerilla campaigns satirically imitate the format of real ones, in Bogad’s words, "they become more about the central celebrity and less about the affinity group." For example, JettBlakk marched in St. Patrick’s Day parades, crashed formal galas to parade with other candidates, and appeared on the floor of the Democratic National Convention in her "Lick Bush in '92" push, all the time dolled up in hot wigs and seven-inch high heels. (Bogad spills a lot of ink on these fashion details.) What was JettBlakk's platform?

"My platforms, why tell you about them when you can see them for

yourself? There they are, I walk on them every day. I'd like to see

Bill (Clinton) wear these."