May 06

May 06

France’s Jewish Prophets: Alain Finkielkraut, Albert Memmi, and the Looming Crisis of Liberalism

Dr. Michael Shurkin

French Jews have long had a privileged relationship with their country’s intellectual life. Sometime they have been an object of intellectual effervescence – as at the time of the Dreyfus Affair, which occasioned the invention of the very term “intellectual” – and sometimes, as Jonathan Judaken has recently noted, they have been the standard bearers of the French tradition of the public intellectual, as when figures such as Bernard-Henri Lévy fulfilled the role of prescient Jeremiah (and more) in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

French Jews have long had a privileged relationship with their country’s intellectual life. Sometime they have been an object of intellectual effervescence – as at the time of the Dreyfus Affair, which occasioned the invention of the very term “intellectual” – and sometimes, as Jonathan Judaken has recently noted, they have been the standard bearers of the French tradition of the public intellectual, as when figures such as Bernard-Henri Lévy fulfilled the role of prescient Jeremiah (and more) in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

That tradition is alive and well, although it has recently taken an unusual turn. Currently a handful of French-Jewish intellectuals are fighting a battle in which theirs are virtually the only voices of dissent against a crippling liberal consensus known in French as the “pensée unique,” a movement of thought that severely constricts the range of perspectives permitted within French academia, the French press, and French political culture alike. These Jewish philosophes are generally of a rightward bent, although they have no truck with France’s traditional conservative ideologies, which, rooted in the country’s long counter-revolutionary traditions and indelibly stained by the anti-Dreyfus movement and Vichy, offer Jews no home. Rather, they are not unlike America’s neo-conservatives – apostate Leftists who once rallied to the 1968 student movement but who now critique the Left, albeit in the name of the Enlightenment values that, they argue, the Left too readily betrays. They define themselves as sworn enemies of totalitarianism in all its forms, and, unlike American neo-cons, evoke a kind of liberalism which, while familiar to Americans and Britons, never really took root south of the Channel, and reflects a morals-based approach that eschews doctrine. Finally, and perhaps fatally for the French-Jewish intellectual tradition, these new intellectuals have increasingly evinced a touch of what might be called the Pym Fortuyn Syndrome: a fear of Islam and Islamism based on the threat they pose to liberal culture.

Naming Names

Who are these Jewish intellectuals? The anti-Semitic Genevan Imam Tariq Ramadan provided a fine list in an October 2003 rant liberally reprinted in Le Monde and elsewhere: Alain Finkielkraut, Alexandre Adler, Bernard Kouchner, André Glucksmann, Pierre-André Taguieff (who isn’t actually Jewish), and Bernard-Henri Lévy [see article], all accused by Ramadan of supporting Israel and the American-led war in Iraq. Says Ramadan, these sins indicate that this group of intellectuals is guilty of betraying the French Enlightenment’s universal values in favor of the Jewish communities’ particular interests. Indeed, in Ramadan's rant -- published in the leading French newspaper of the day -- they are all agents of Ariel Sharon, working in parallel to the Jewish cell controlling American foreign policy.

Ramadan's remarks were invited by Le Monde, whose editorial policies themselves occasionally flirt with antisemitism and which, in March 2003, itself ran a list of the same intellectuals under the title “In France, these intellectuals who say ‘yes’ to war.” Without addressing the many differences of opinion and even reservations about the war that separate the individuals in question, Le Monde included in its list (together with several others) most of the same figures: André Glucksmann, Pascal Bruckner, Romain Goupil, Bernard Kouchner, Alain Finkielkraut, Jacky Mamou, Pierre Lellouche, Michel Taubmann, and Shmuel Trigano. All of them happen to be Jewish.

The war in Iraq is indeed one of the issues on which France’s Jewish intellectuals distinguish themselves, although their positions tend to be far more ambivalent than "yes to war." Rather, the usual argument is that the war, whatever its disadvantages, is at least  morally correct insofar as Saddam Hussein was an evil genocidal tyrant whom the French should be ashamed to have once supported. Bernard-Henri Lévy, for example, has frankly and consistently condemned the war on pragmatic grounds, foremost among them that the United States went after the wrong target. Yet he wrote this past March that the war’s morality was nonetheless “unattackable.”

morally correct insofar as Saddam Hussein was an evil genocidal tyrant whom the French should be ashamed to have once supported. Bernard-Henri Lévy, for example, has frankly and consistently condemned the war on pragmatic grounds, foremost among them that the United States went after the wrong target. Yet he wrote this past March that the war’s morality was nonetheless “unattackable.”

More than the Iraq war, however, it is the question of immigration that looms as France’s greatest challenge, and it is on that issue that France's Jewish intellectuals are marking their greatest distance from the country’s liberal consensus. Two figures in particular stand out: Albert Memmi, the venerable fellow traveler of Jean-Paul Sartre whose leftist, third-worldist credentials are indisputable, and Alain Finkielkraut, who made his career defending the universalist orthodoxy of French Republicanism (itself a particularly Jewish career in the spirit of Adolphe Crémieux and Léon Blum). Both have sounded the alarm against the perceived perils posed by the Muslim community. For various reasons, Memmi escaped public wrath, and Finkielkraut was not so lucky.

Memmi Takes Stock

Albert Memmi made his name in 1957 when he published Portrait of a Colonized/Portrait of a Colonizer, a book which dissects with extraordinary clarity the reciprocal pathologies of colonialism [see article]. As a former indigenous subject of French rule in colonial Tunisia, Memmi always insisted on his place alongside the colonized, whose cause he never doubted. However, he also insisted that after decolonization the burden fell upon the formerly colonized peoples to transcend the circumstances which the colonizers had bequeathed to them. They also had to heal themselves.

Almost fifty years later, Memmi has cast a scornful eye on the former colonized peoples of the world, and concluded that they had made little progress. In 2004, he wrote Portrait of the Decolonized to describe the  failure of decolonized peoples to move beyond their traumas and cease being defined by the colonial experience. Fifty years after independence, Memmi notes in the book, most former colonies are actually even worse off than they were under European tutelage, with political, economic and cultural conditions all having decayed. Memmi has little patience for the reflexive excuses often made in its defense – mystifications, as he describes them, that explain problems most often in terms of the persistence of colonial power and the traumas of colonial rule:

failure of decolonized peoples to move beyond their traumas and cease being defined by the colonial experience. Fifty years after independence, Memmi notes in the book, most former colonies are actually even worse off than they were under European tutelage, with political, economic and cultural conditions all having decayed. Memmi has little patience for the reflexive excuses often made in its defense – mystifications, as he describes them, that explain problems most often in terms of the persistence of colonial power and the traumas of colonial rule:

The young nations have been independent for fifty years; they have had all the time necessary to reform themselves and to erase, if they really wanted to, the negative after-effects of their earlier state of subjugation.

Memmi, Portrait of a Colonized, pp. 83-84

Memmi's strongest attacks are on the “Arabo-Muslim” world, which he derides as fundamentally “sick,” particularly in light of their indulgence of terrorism and suicide bombings.

If one can employ here the language of medicine, one could say that Arabo-Muslim society suffers from a grave depressive syndrome that prevents it from perceiving an escape from its current state. The Arab world still has not discovered, or wanted to consider, the transformations that would finally adapt it to the modern world that is coming at it from all directions. Instead of examining itself, and in function of this diagnostic, of taking the remedies required, it searches in others the causes of its disfunctions. It is the fault of the Americans, or the Jews, the miscreants, the infidels, the multinationals…Through a classic phenomenon of projection, the Arab world also blames others for all sins, depravations, loss of values, materialism, atheism, etc.

Id., pp. 33-36

The Arab-Israeli conflict, Memmi claims, is just an excuse. Calling it minor by every measure when compared to so many of the planet’s other conflicts, Memmi claims that it “illustrates and supports two myths of compensation and revindication that are always alive among the Arabs,” first that “if the Arabs unified they would be able to become again a power comparable if not superior to that of their past empires,” and second that Israel is all that stands in their way. Together, Memmi says, the two myths have sustained Arab passions while diverting them from more constructive pursuits, a problem he links to the “resignation” of intellectuals in the Arab world, who are incapable or unwilling to break with their societies’ dogma and taboos.

Arabo-Muslim intellectuals finally have to lean on a tradition other than submission to dogma and power and lining up with public opinion. Or, there no longer exists, if it ever existed, in the Arabo-Muslim world, this great public tribunal necessary for democracy where each can, contradictorily, express his opinion without excessive risk.

Id., p. 49

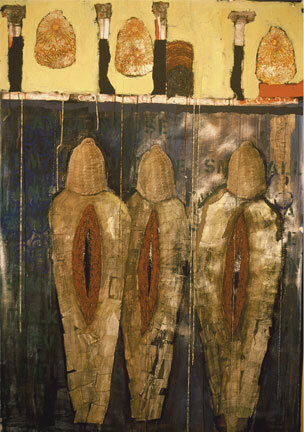

Middle: Jean Benabou, Baskets

Lower: Albert Memmi